Introduction

For those who are not familiar with Assembly, I've written an additional article where I explain Assembly Instructions in Intel x86 syntax. After reading this article, you can continue with the Binary Exploitation basics.

Data Movement Instructions

mov

The mov instruction facilitates the transfer of data. It copies the data item referenced by its second operand (such as register contents, memory contents, or a constant value) into the location specified by its first operand (a register or memory). While register-to-register moves are feasible, direct memory-to-memory moves are not supported. When memory transfers are necessary, the source memory contents must initially be loaded into a register, which can then be stored at the destination memory address.

Syntax

mov <reg>,<reg>

mov <reg>,<mem>

mov <mem>,<reg>

mov <reg>,<const>

mov <mem>,<const>

Examples

mov eax, ebx ; Copy the value in ebx into eax.

mov byte ptr [var], 5 ; Store the value 5 into the byte at location var.

push

The push instruction serves to push its operand onto the top of the hardware-supported stack in memory. It begins by decrementing ESP by 4 and then places its operand into the contents of the 32-bit location at address ESP. ESP (the stack pointer) is decremented by push since the x86 stack grows downward, meaning the stack expands from higher addresses to lower addresses.

Syntax

push <reg32>

push <mem>

push <con32>

Examples

push eax ; Push eax onto the stack.

push [var] ; Push the 4 bytes at address var onto the stack.

pop

The pop instruction extracts the 4-byte data element from the top of the hardware-supported stack into the specified operand (either a register or a memory location). It begins by transferring the 4 bytes located at memory location ESP into the specified register or memory location, followed by an increment of ESP by 4.

Syntax

pop <reg32>

pop <mem>

Examples

pop edi ; Pop the top element of the stack into EDI.

pop [ebx] ; Pop the top element of the stack into memory at the four bytes starting at location EBX.

lea

The lea (Load Effective Address) instruction assigns the address specified by its second operand to the register specified by its first operand. Note that it merely computes and assigns the effective address, without loading the contents of the memory location. This functionality is particularly useful for obtaining a pointer into a memory region.

Syntax

lea <reg32>,<mem>

Examples

lea edi, [ebx+4_esi] ; Place the quantity EBX+4_ESI into EDI.

lea eax, [var] ; Place the value in var into EAX.

lea eax, [val] ; Place the value val into EAX.

Arithmetic and Logic Instructions

add

Integer Addition The add instruction combines its two operands, storing the result in the first operand. It's noteworthy that both operands may be registers, but only one operand can be a memory location.

Syntax

add <reg>,<reg>

add <reg>,<mem>

add <mem>,<reg>

add <reg>,<con>

add <mem>,<con>

Examples

add eax, 10 ; EAX ← EAX + 10

add BYTE PTR [var], 10 ; Add 10 to the single byte stored at memory address var.

sub

Integer Subtraction The sub instruction subtracts the value of its second operand from the value of its first operand and stores the result in the first operand.

Syntax

sub <reg>,<reg>

sub <reg>,<mem>

sub <mem>,<reg>

sub <reg>,<con>

sub <mem>,<con>

Examples

sub eax, 216 ; Subtract 216 from the value stored in EAX.

and, or, xor

Bitwise Logical Operations: These instructions perform bitwise logical operations on their operands, placing the result in the first operand location.

Syntax

and, or, xor <reg>,<reg>

and, or, xor <reg>,<mem>

and, or, xor <mem>,<reg>

and, or, xor <reg>,<con>

and, or, xor <mem>,<con>

Examples

and eax, 0fH ; Clear all but the last 4 bits of EAX.

xor edx, edx ; Set the contents of EDX to zero.

Flow Control Instructions

In x86 architecture, the Instruction Pointer (IP) register is pivotal, indicating the memory location where the current instruction starts. Typically, it advances to the subsequent instruction in memory post-execution. Direct manipulation of the IP register is prohibited; instead, it's implicitly updated by dedicated control flow instructions.

For convenient referencing within the program text, we utilize labels denoted by <label>. These labels, marked by a colon after a name, can be inserted anywhere in the x86 assembly code. For instance,

mov esi, [ebp+8]

begin: xor ecx, ecx

mov eax, [esi]

In this snippet, the second instruction is labeled "begin." Throughout the code, we can refer to the memory location of this instruction using the symbolic name "begin," providing a more manageable representation than its 32-bit value.

jmp — Jump

This instruction redirects program flow to the memory location specified by the operand.

Syntax

jmp <label>

Example

jmp begin ; Jumps to the instruction labeled "begin."

Conditional Jumps

These instructions enable conditional jumps based on the state of condition codes stored in the Machine Status Word, a special register retaining information about the last arithmetic operation. For instance, one bit signifies whether the last result was zero, while another indicates negativity. Various conditional jumps can be executed based on these condition codes. For example, the "jz" instruction jumps to the specified label if the last arithmetic operation yielded zero; otherwise, control proceeds sequentially.

Syntax

je <label> ; (jump if equal)

jne <label> ; (jump if not equal)

jz <label> ; (jump if last result was zero)

jg <label> ; (jump if greater than)

jge <label> ; (jump if greater than or equal to)

jl <label> ; (jump if less than)

jle <label> ; (jump if less than or equal to)

Example

cmp eax, ebx

jle done

If the contents of EAX are less than or equal to the contents of EBX, the program jumps to the label "done"; otherwise, it continues to the next instruction.

cmp — Compare

This instruction compares the values of two specified operands, adjusting the condition codes in the Machine Status Word accordingly. Functionally akin to the "sub" instruction, it discards the subtraction result instead of replacing the first operand.

Syntax

cmp <reg>,<reg> ;

cmp <reg>,<mem> ;

cmp <mem>,<reg> ;

cmp <reg>,<con> ;

Example

cmp DWORD PTR [var], 10

jeq loop

If the 4-byte value stored at memory location "var" equals the integer constant 10, the program jumps to the label "loop."

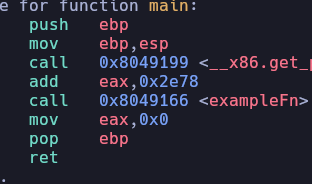

call, ret — Subroutine Call and Return

These instructions facilitate subroutine invocation and return. The "call" instruction first pushes the current code location onto the stack in memory, then unconditionally jumps to the specified code location. Unlike simple jump instructions, "call" saves the return location for subroutine completion.

The "ret" instruction implements the subroutine return mechanism. It first pops a code location off the stack, then unconditionally jumps to the retrieved location.

In simpler terms, the call instruction saves the current location by pushing the value of the instruction pointer onto the stack and then redirects the program execution to the specified subroutine. On the other hand, the ret instruction retrieves the address previously saved by call from the stack to the instruction pointer, effectively returning control to the main program from the completed subroutine.

Syntax

call <label>

ret

leave

The LEAVE instruction copies the frame pointer (in the EBP register) into the stack pointer register (ESP), which releases the stack space allocated to the stack frame. The old frame pointer (the frame pointer for the calling procedure that was saved by the ENTER instruction) is then popped from the stack into the EBP register, restoring the calling procedure’s stack frame.

A RET instruction is commonly executed following a LEAVE instruction to return program control to the calling procedure.

enter

The enter instruction is used to set up a stack frame for a procedure. It allocates space on the stack for local variables and dynamically allocated storage and establishes a new base pointer (EBP) for accessing these variables within the procedure. Additionally, it provides support for nested procedures by adjusting the stack frame according to the lexical nesting level.

You'll notice that this instruction is not called in the programs we'll analyse, however, it's commonly replaced with three instructions:

push ebp ; Save the current base pointer

mov ebp, esp ; Set the base pointer to the current stack pointer

sub esp, imm32 ; Allocate space for local variables and dynamic storage

nop

This instruction performs no operation. It is a one-byte or multi-byte NOP that takes up space in the instruction stream but does not impact machine context, except for the EIP register.

Continuing with Binary Exploitation basics

Once you've read this article, you can continue reading the Binary Exploitation basics.

References

https://www.cs.virginia.edu/~evans/cs216/guides/x86.html

https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/leave

https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/enter

https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/nop